are-we-flying

Flying planes with JavaScript

To allay any concerns: this is not about running JavaScript software to control an actual aircraft.

That would kill people.

Instead, we’re writing a web page that can control an autopilot running in JS that, in turn, controls a little virtual aeroplane. And by “little” I actually mean “most aeroplanes in Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020” because as it turns out, MSFS comes with an API that can be used to both query *and set* values ranging from anything as simple as cockpit lights to something as complex as spawning a fleet of aircraft and making them fly in formation while making their smoke pattern spell out the works of Chaucer in its original middle English.

While we’re not doing that (…today?), we *are* going to write an autopilot for planes that don’t have one, as well as planes that do have one but that are just a 1950’s chore to work with, while also tacking on some functionality that just straight up doesn’t exist in modern autopilots. The thing that lets us perform this trick is that MSFS comes with something called SimConnect, which is an SDK that lets people write addons for the game using C, C++, or languages with .NET support… and so, of course, folks have been writing connectors to “port” the SimConnect function calls to officially unsupported languages like Go, Node, Python, etc.

Which means that we could, say, write a web page that allows us to see what’s going on in the game. And toggle in-game settings. And –and this is the one that’s the most fun– fly the plane from a web page. And once we’re done “it’ll be that easy” but the road to get there is going to take a little bit of prep work… some of it tedious, some of it weird, but all of it’s going to set us up for just doing absolutely ridiculous things and at the end of it, we’ll have a fully functional autopilot with auto-takeoff and flight planning that’s as easy as using google maps and whatever’s missing, you can probably bolt on yourself!

Before we get there though, let’s start at the start. If the idea is to interface with MSFS from a webpage, and webpages use JS, then your first thought might be “Cool, can I write an express server that connects to MSFS?” to which the answer is: yes! There is the node-simconnect package for Node, which implements full access to the SimConnect DLL file, but it’s very true to the original C++ SDK, meaning it’s a bit like “programming C++ in JavaScript”. Now, you might like that (I don’t know your background) but JS has its own set of conventions that don’t really line up with the C++ way of doing things, and because I know my way around programming and I like writing JS, I created a somewhat more “JavaScripty” API on top of node-simconnect called msfs-simconnect-api-wrapper (I am *great* at naming things) which lets me (and you!) write code that can talk to MSFS in a way that looks and feels much more like standard JavaScript, so… let’s use that!

Also, because we want to talk “from the browser to a game”, we don’t really want to have to rely on HTML GET and POST requests, because they’re both slow, and unidirectional: the game will never be able to talk to us unless it’s to answer a question we sent it. That’s not great, especially not if we want to register event handlers, so instead we’ll use web sockets, which let us set up a persistent bidirectional data connection And to make that a trivial task, we’re going to use a library called “socketless”, which lets us write client/server code as if everything is just local code, and it magically makes things work over the network.

If that sounds cool: you can check out the complete project over on the “Are we flying?” Github repository, and you can just clone that and run the project with a simple run.bat, but if you want to actually learn something… let’s dive in!

The structure of this “tutorial”

We’ll be tackling this whole thing in six parts:

- In the first part we’ll cover the prep work we need to do in order to set up a working combination of MSFS, a SimConnect API server for communicating to and from MSFS, and a web server that hosts a webpage and takes care of communicating to and from the API server.

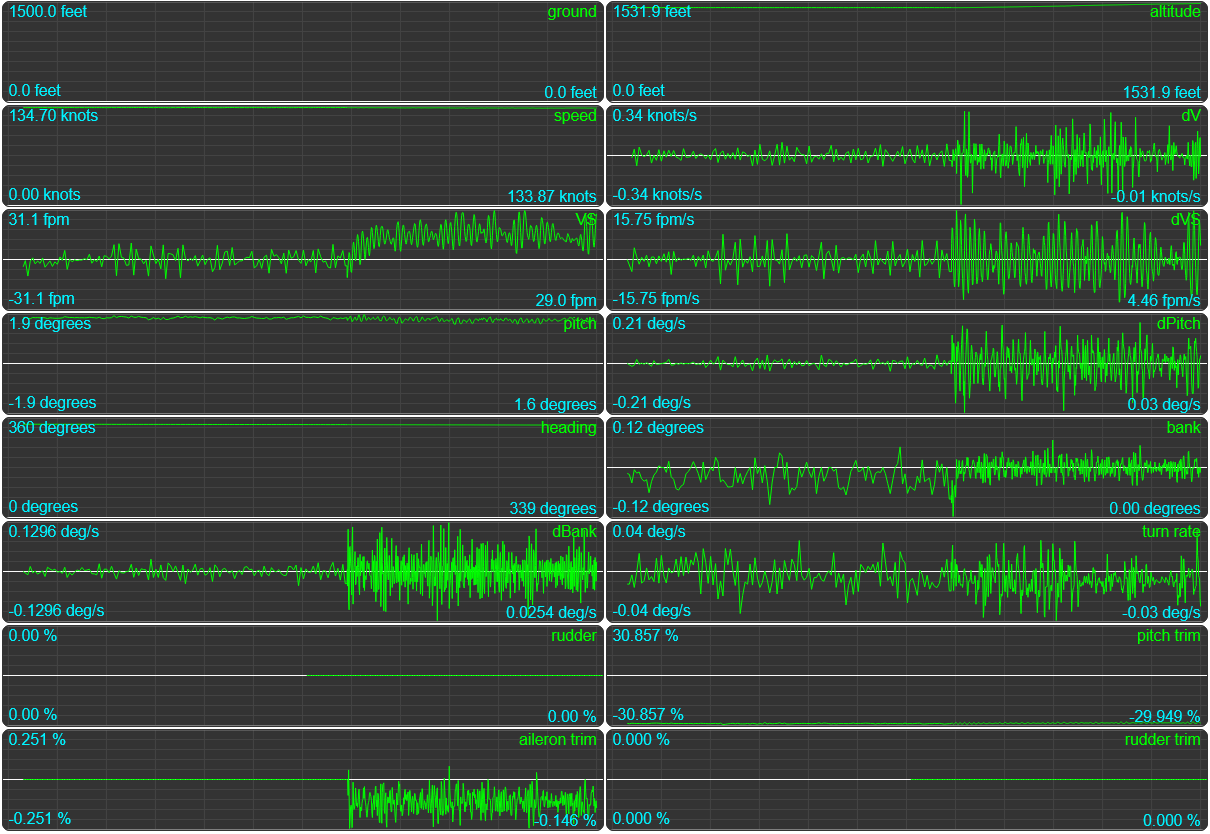

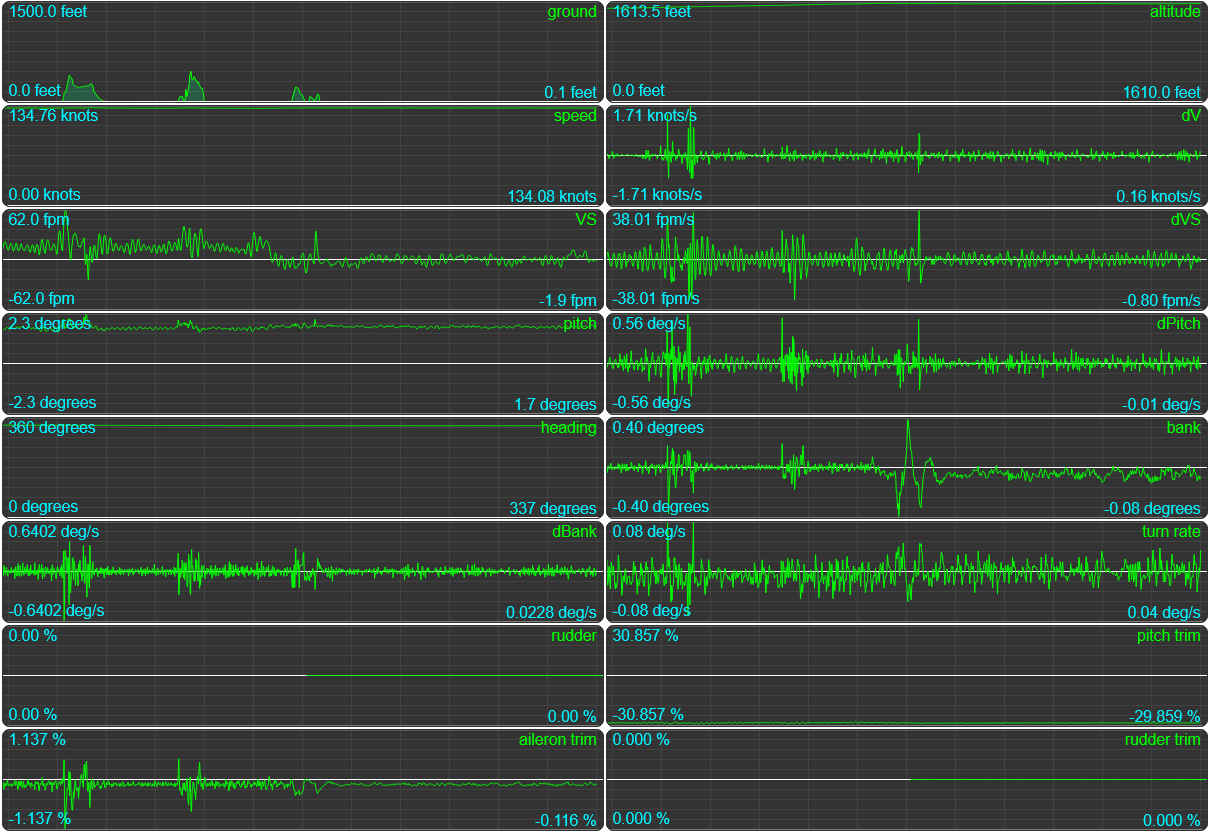

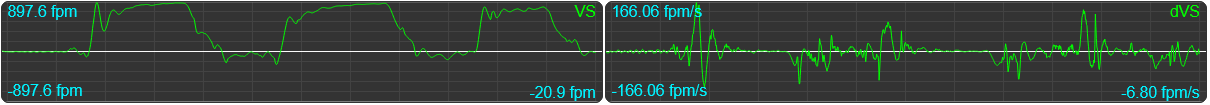

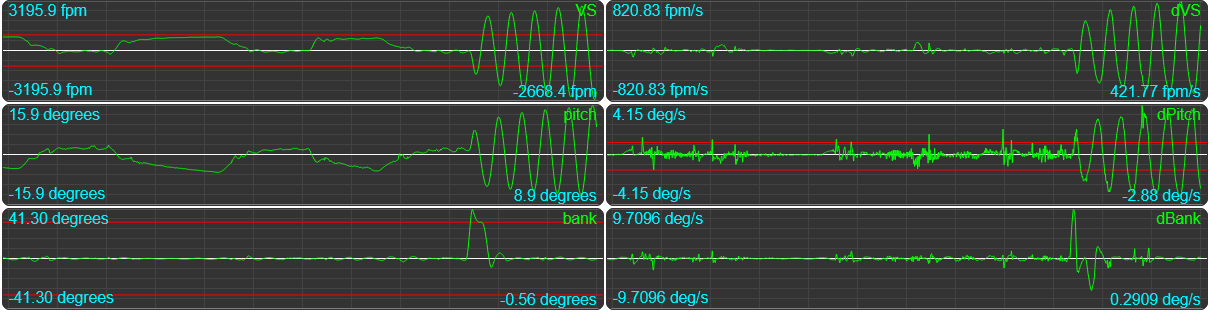

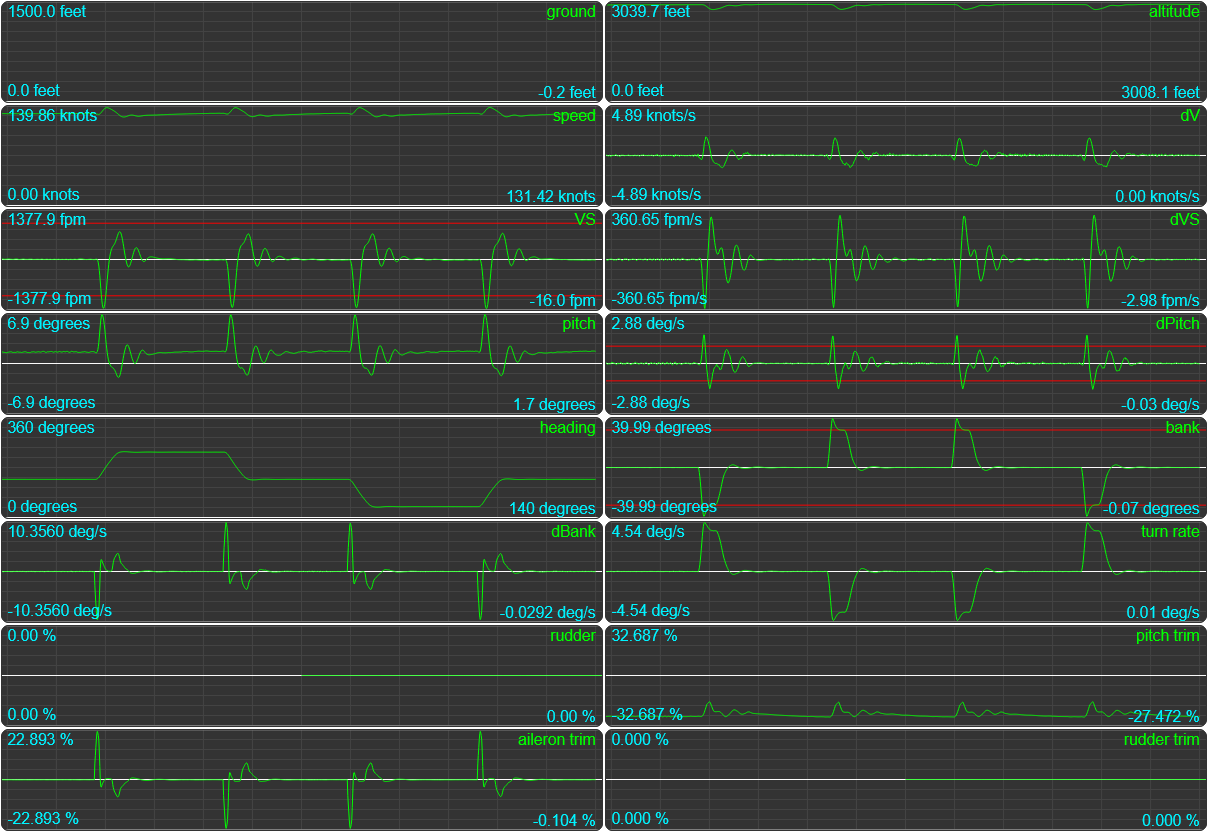

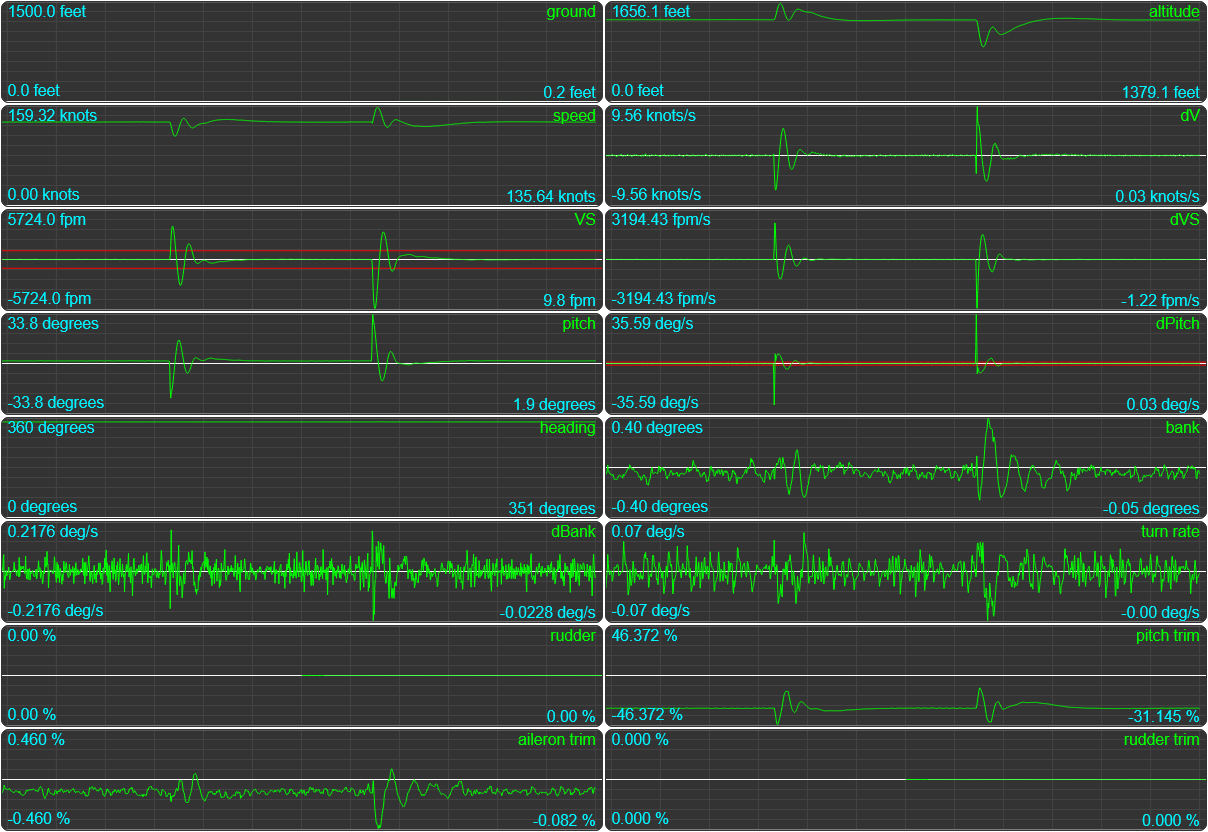

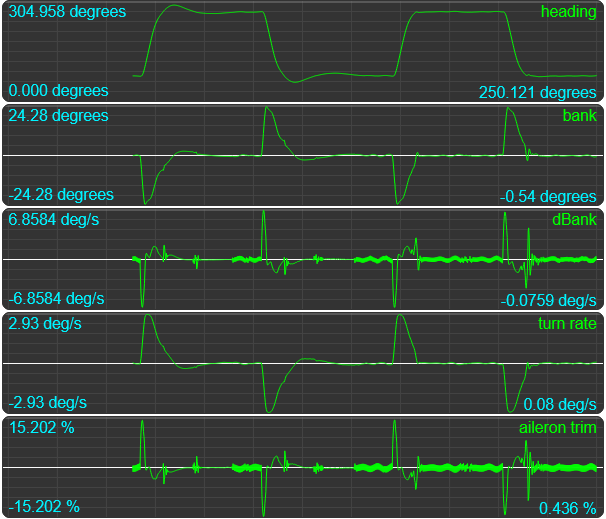

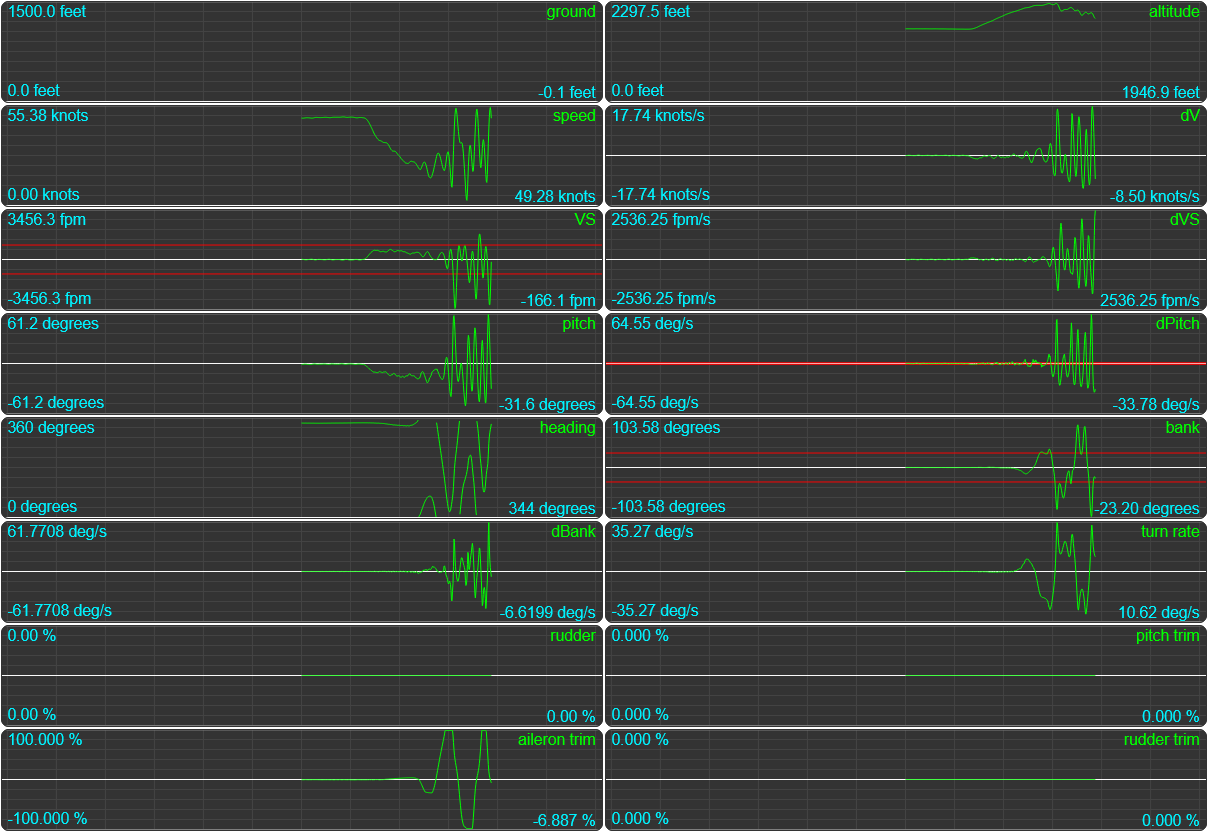

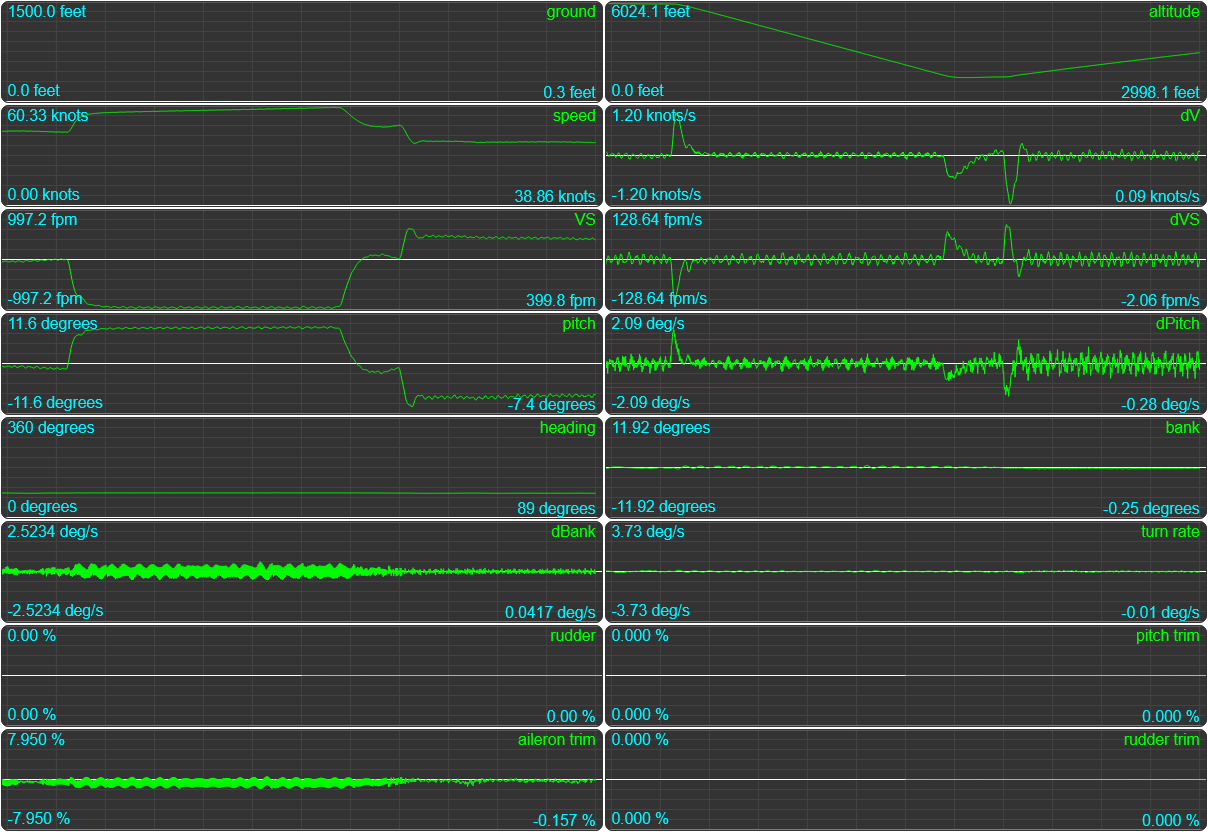

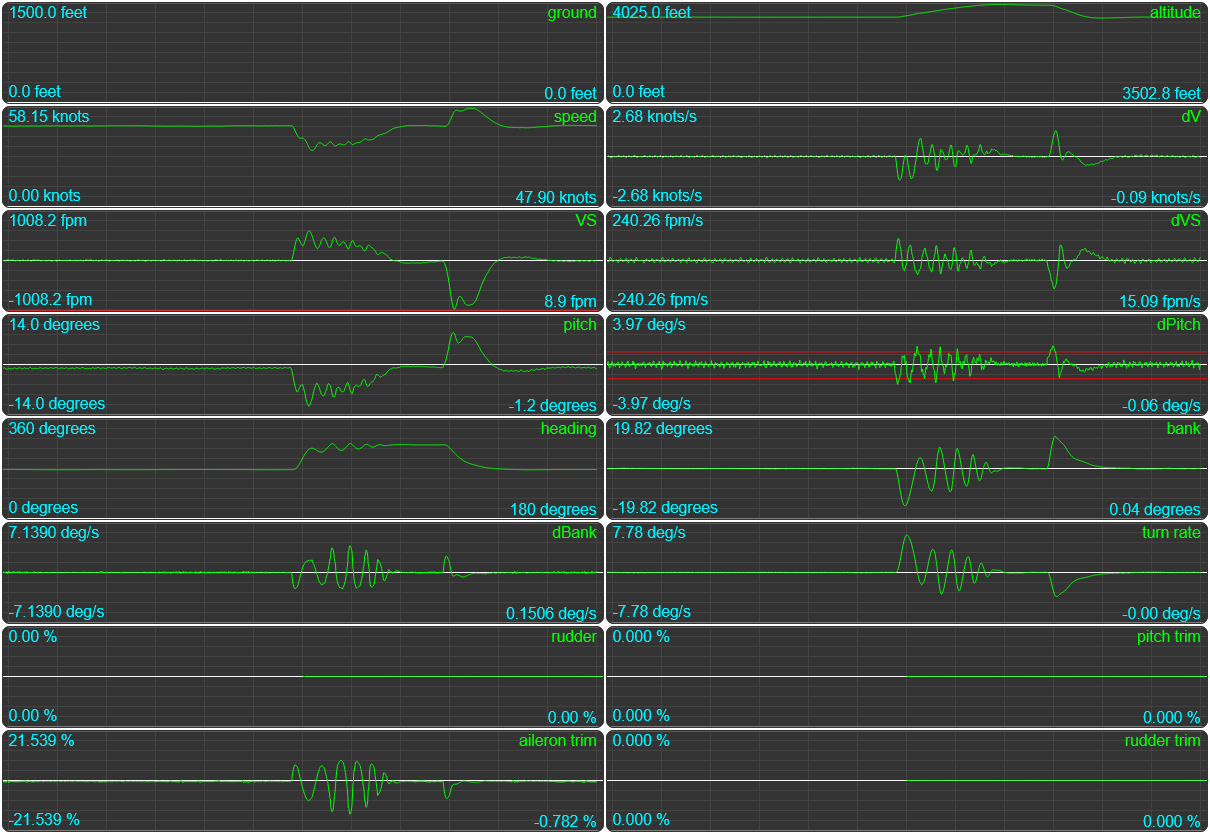

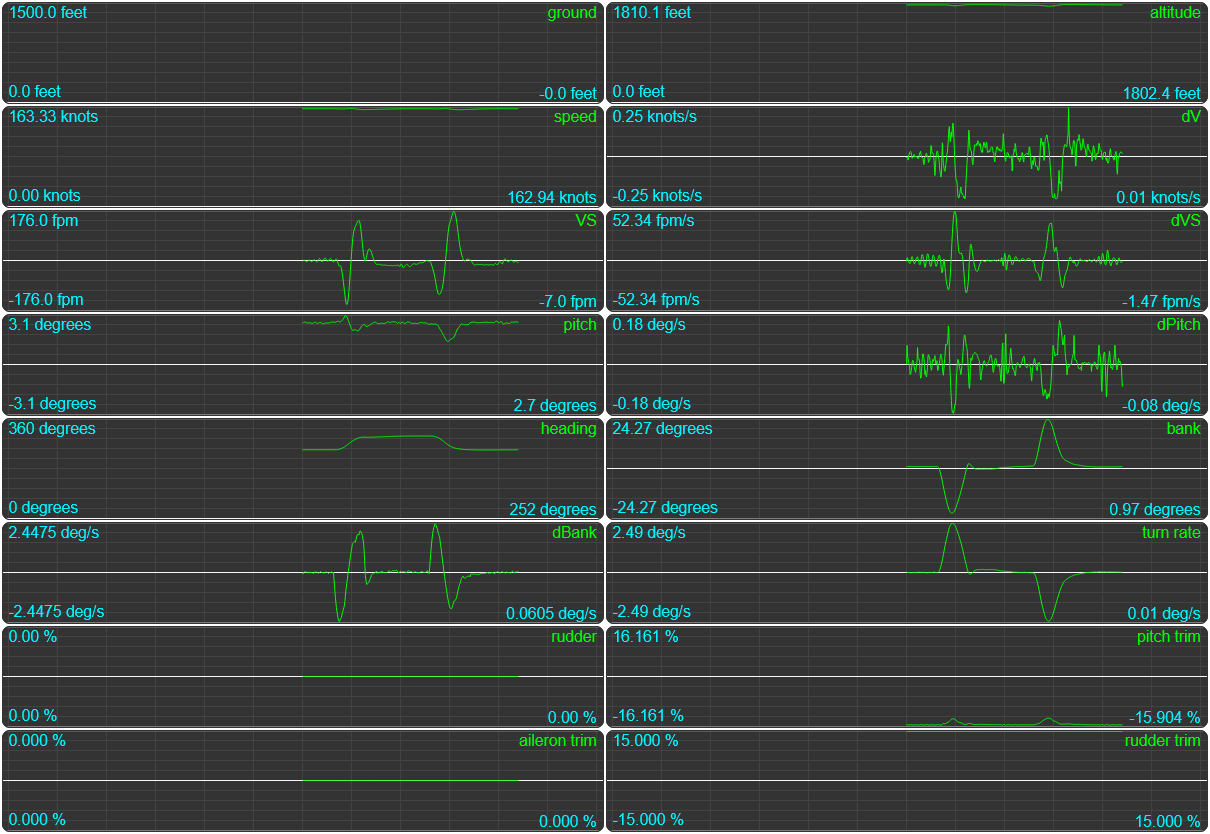

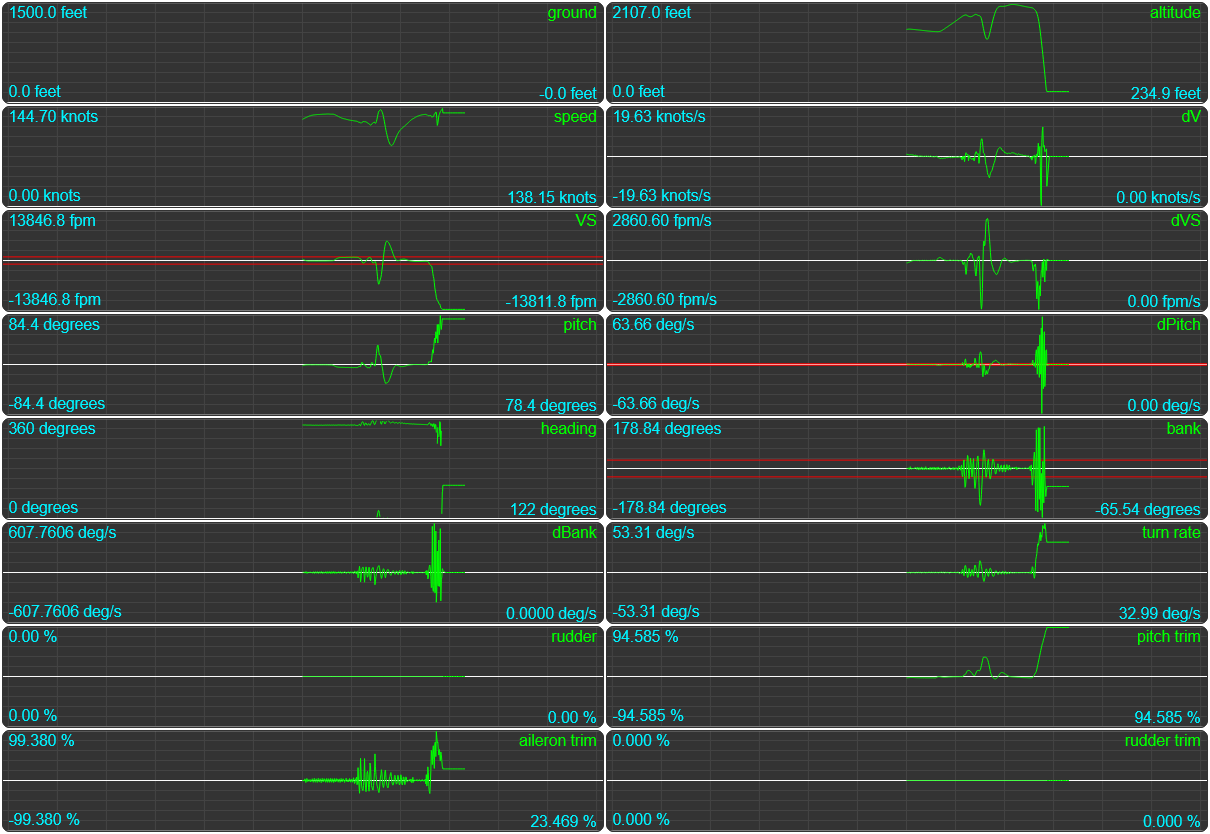

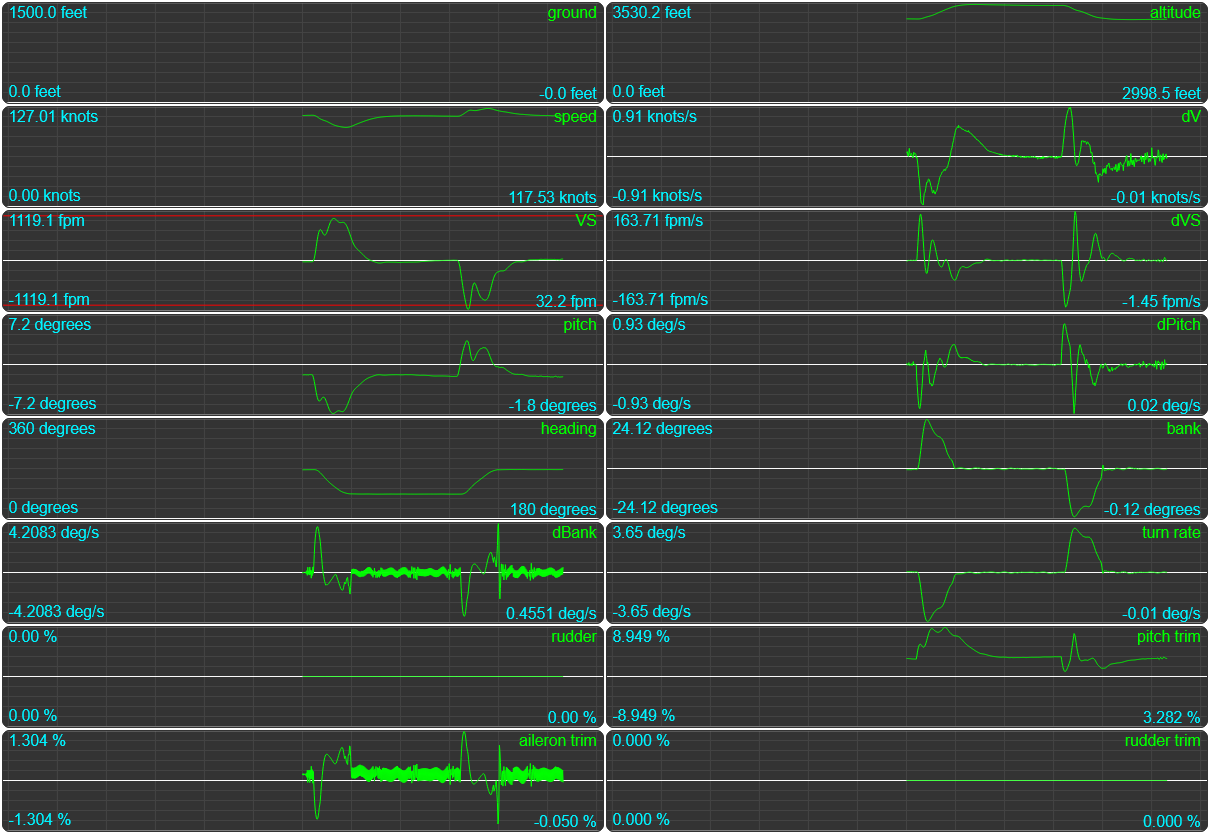

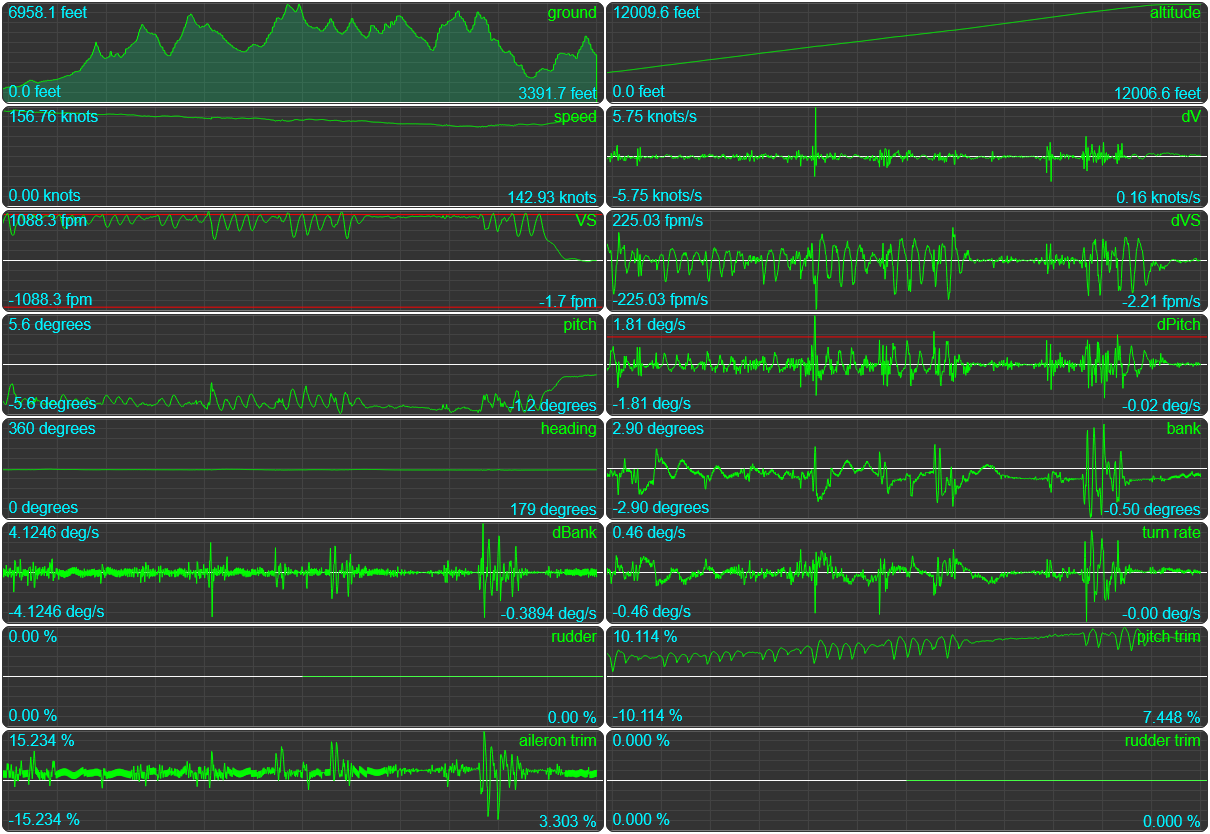

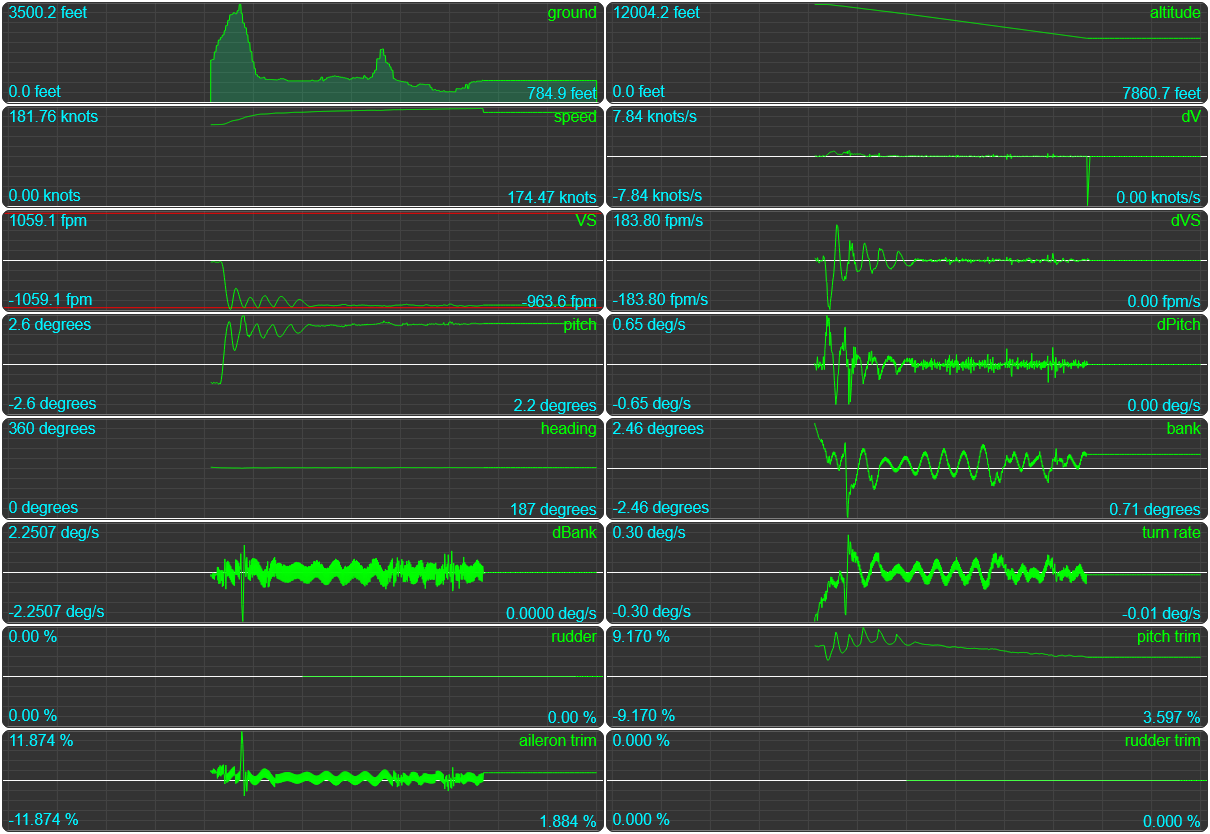

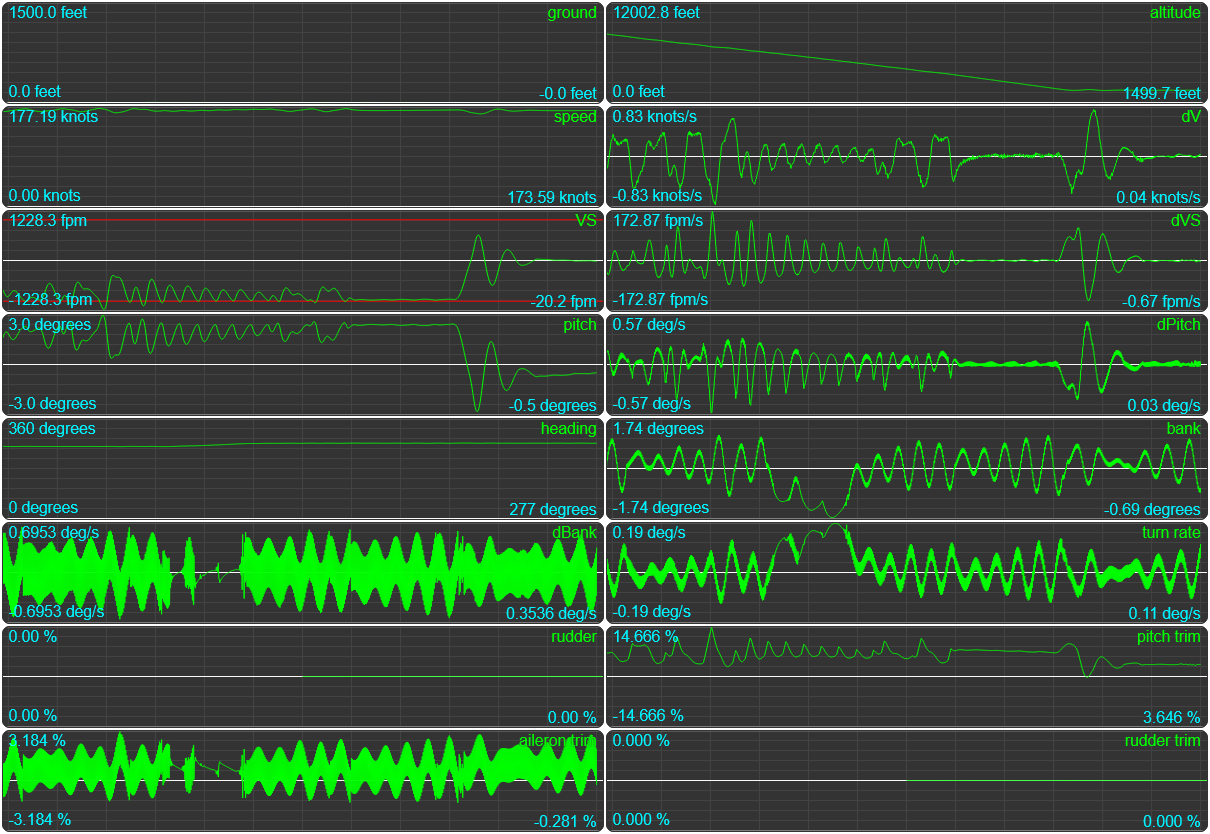

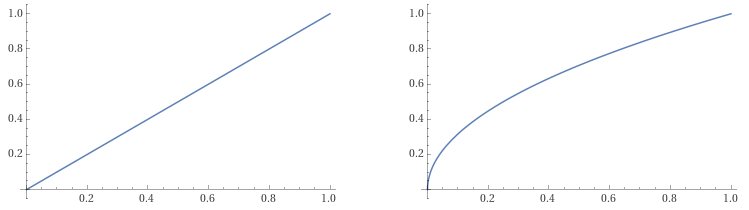

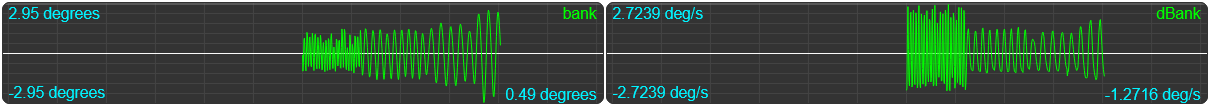

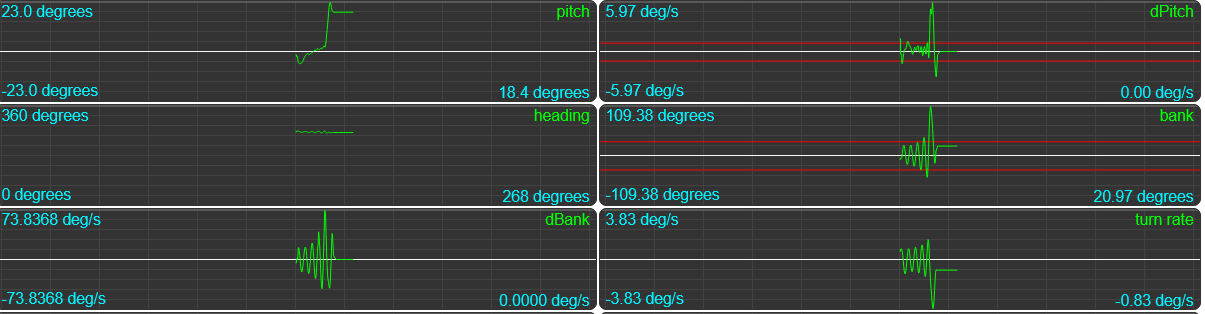

- In the the second part we’ll cover the “web page pages”, where we’re going to visualize everything we can visualize relating to our flights in MSFS, including graphs that plot the various control values over time (altitude, speed, heading, trim values, etc.) to get a better insight into how our aeroplane(s) responds to control inputs.

- In the third part we’ll cover the thing you came here for: writing our own autopilot (in several stages of complexity) and making our computer fly planes all on its own!

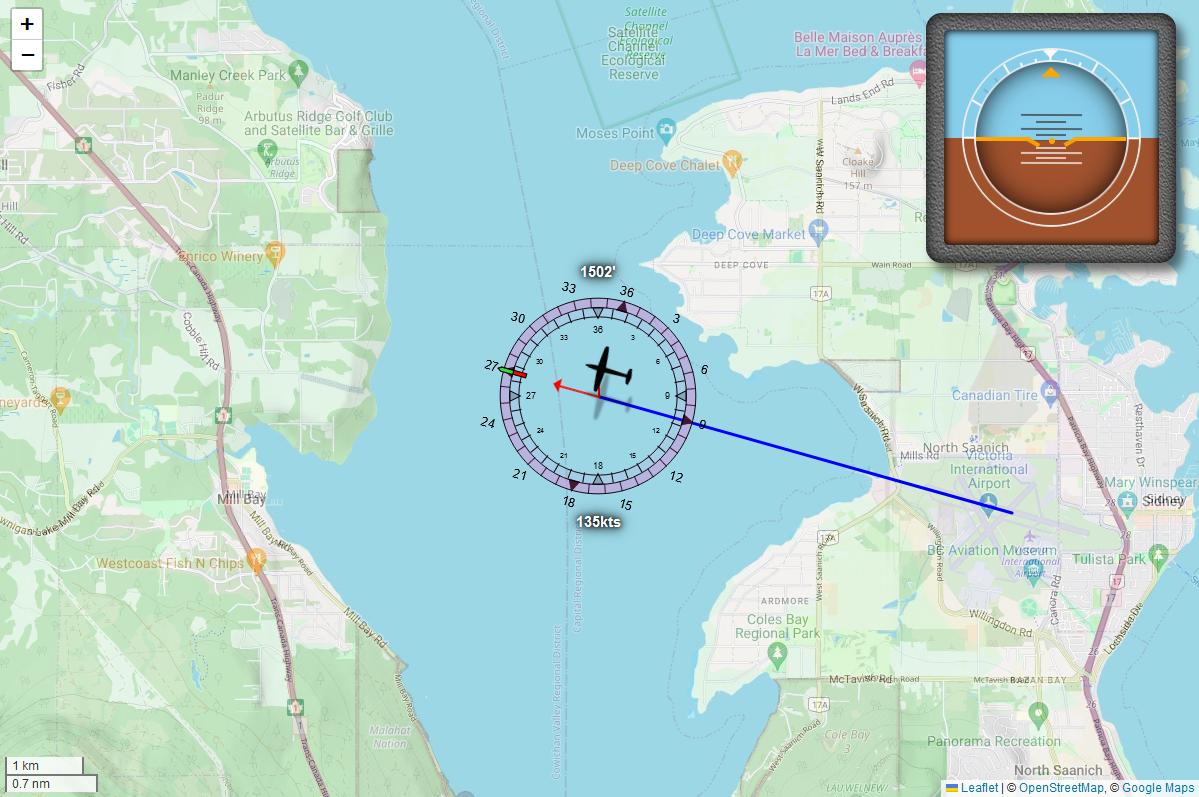

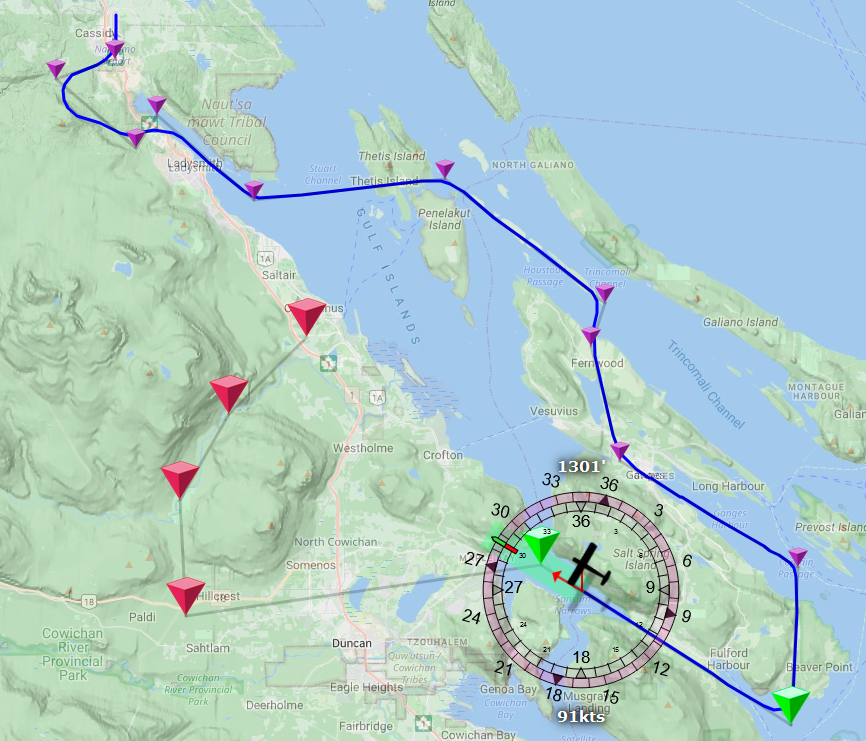

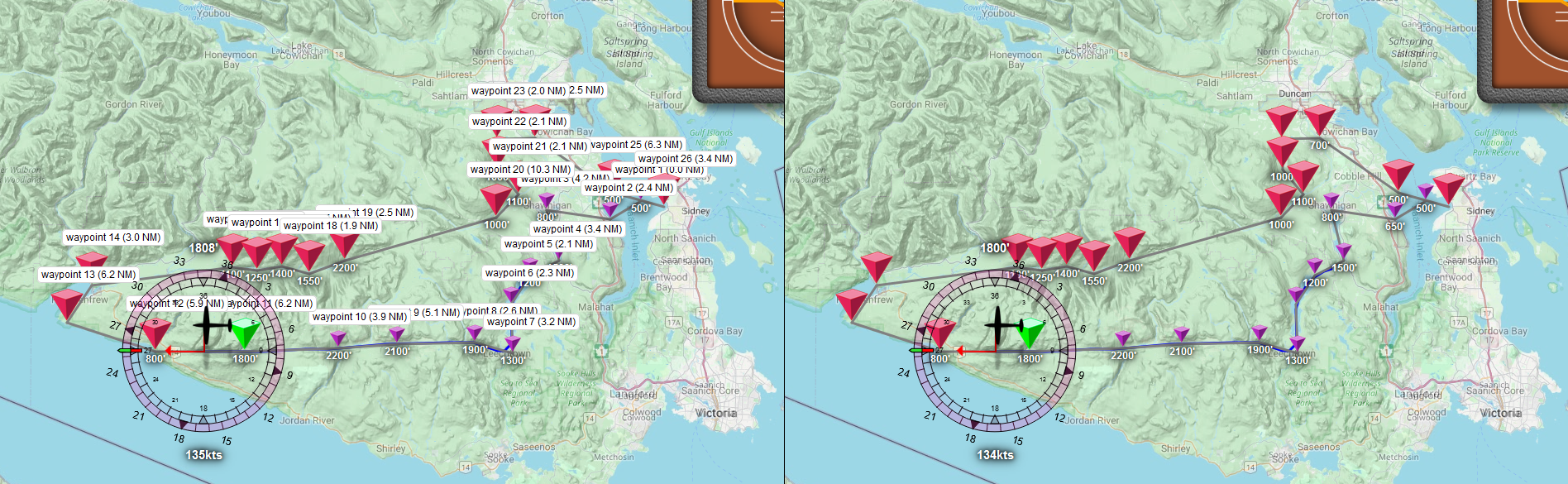

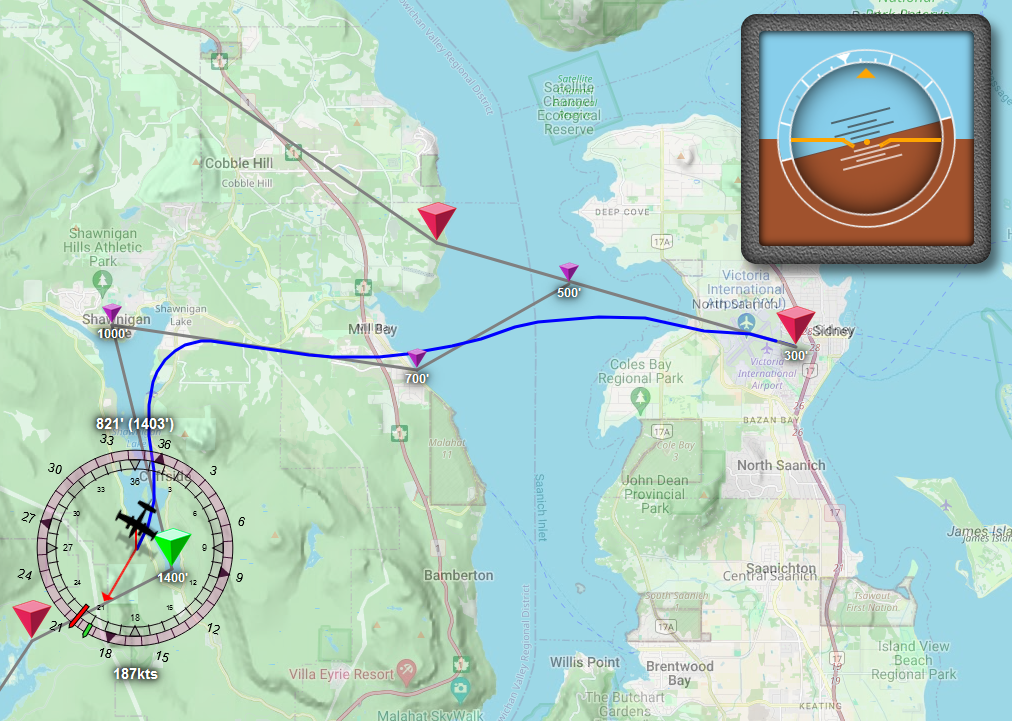

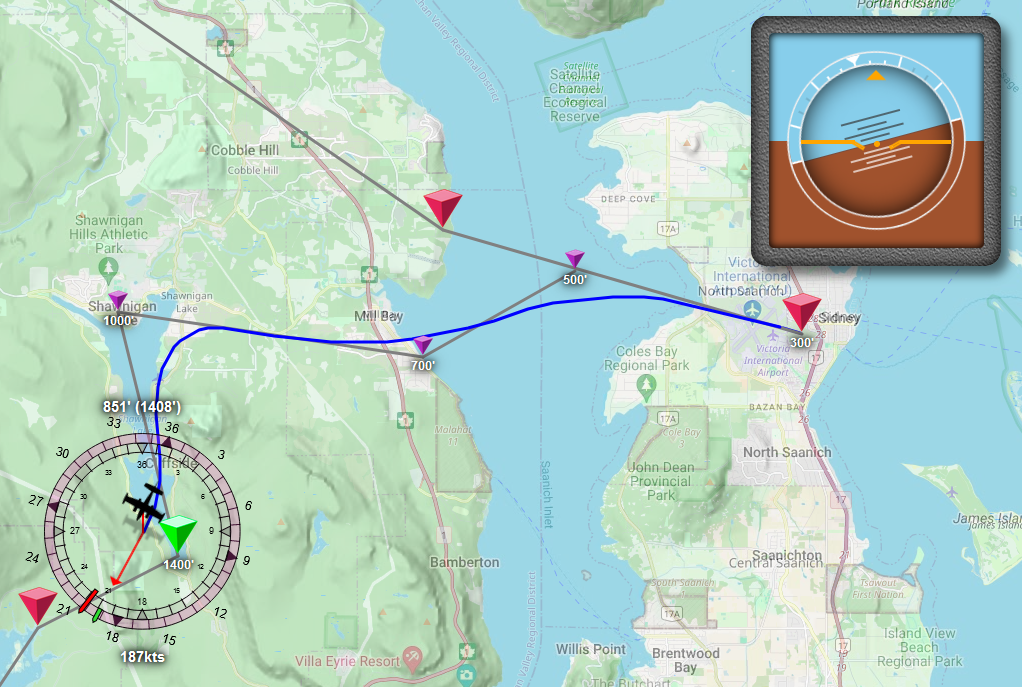

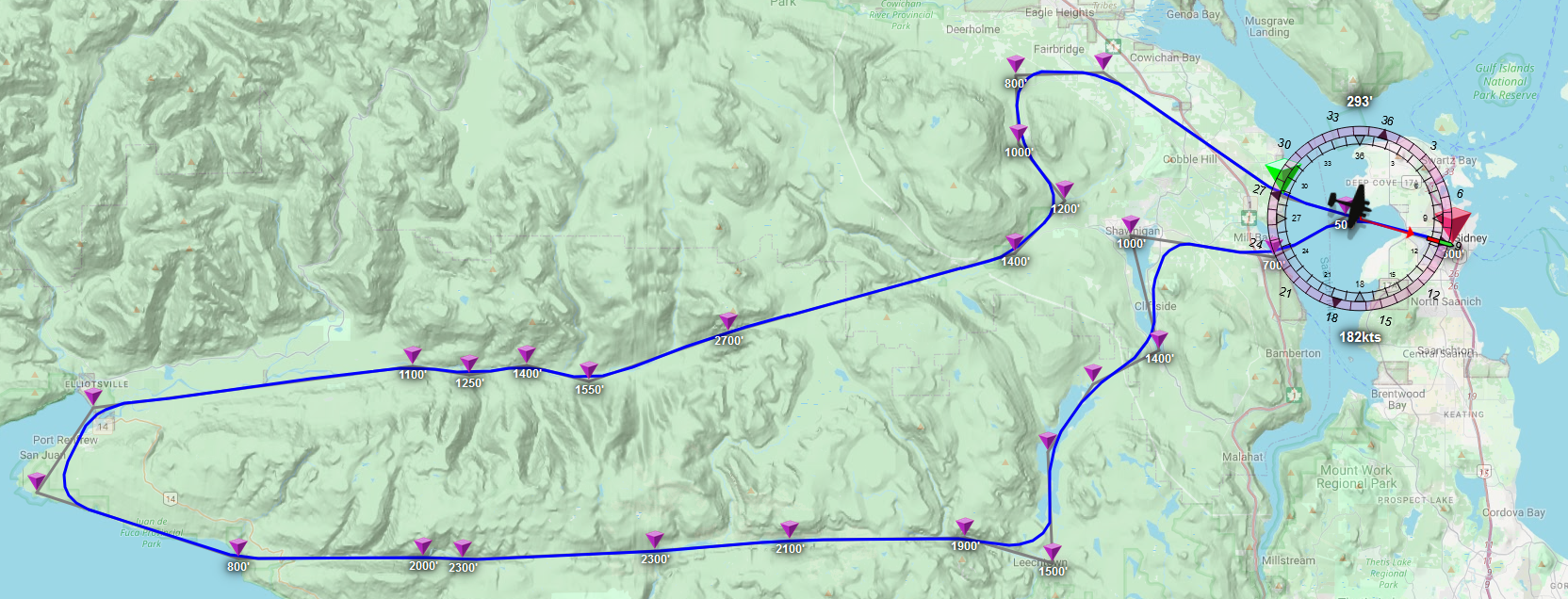

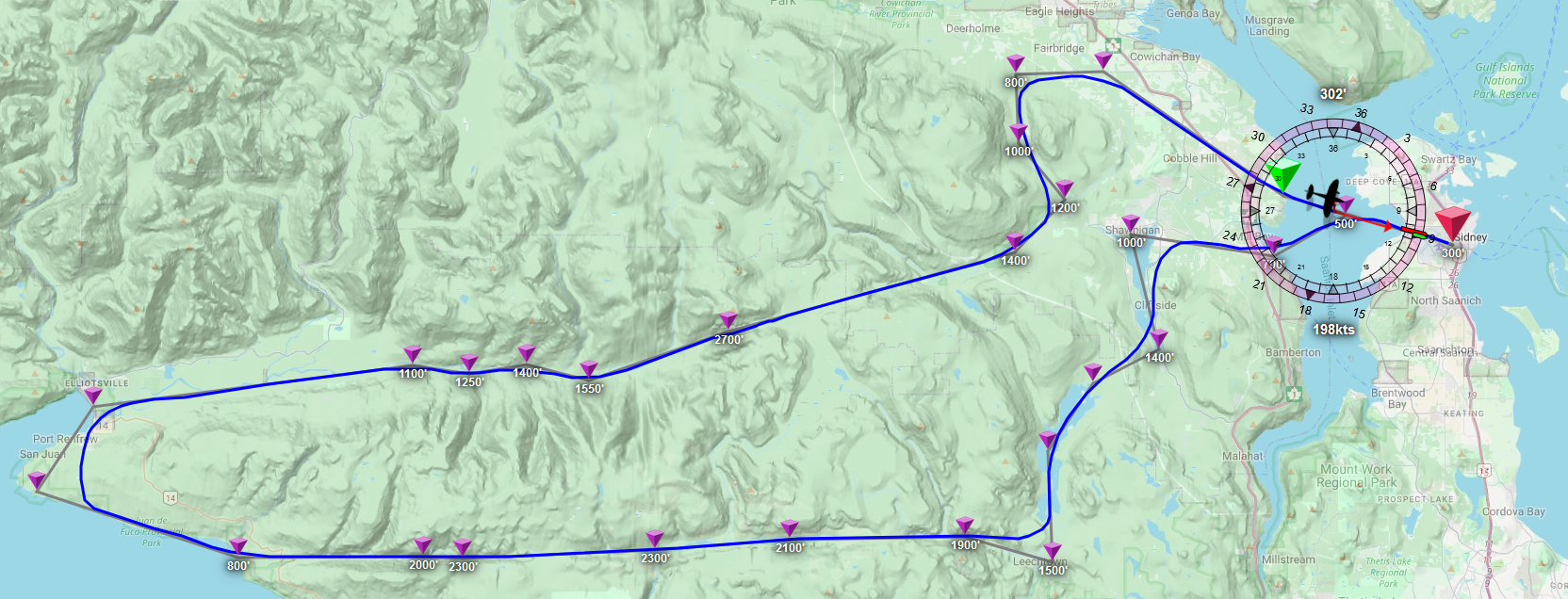

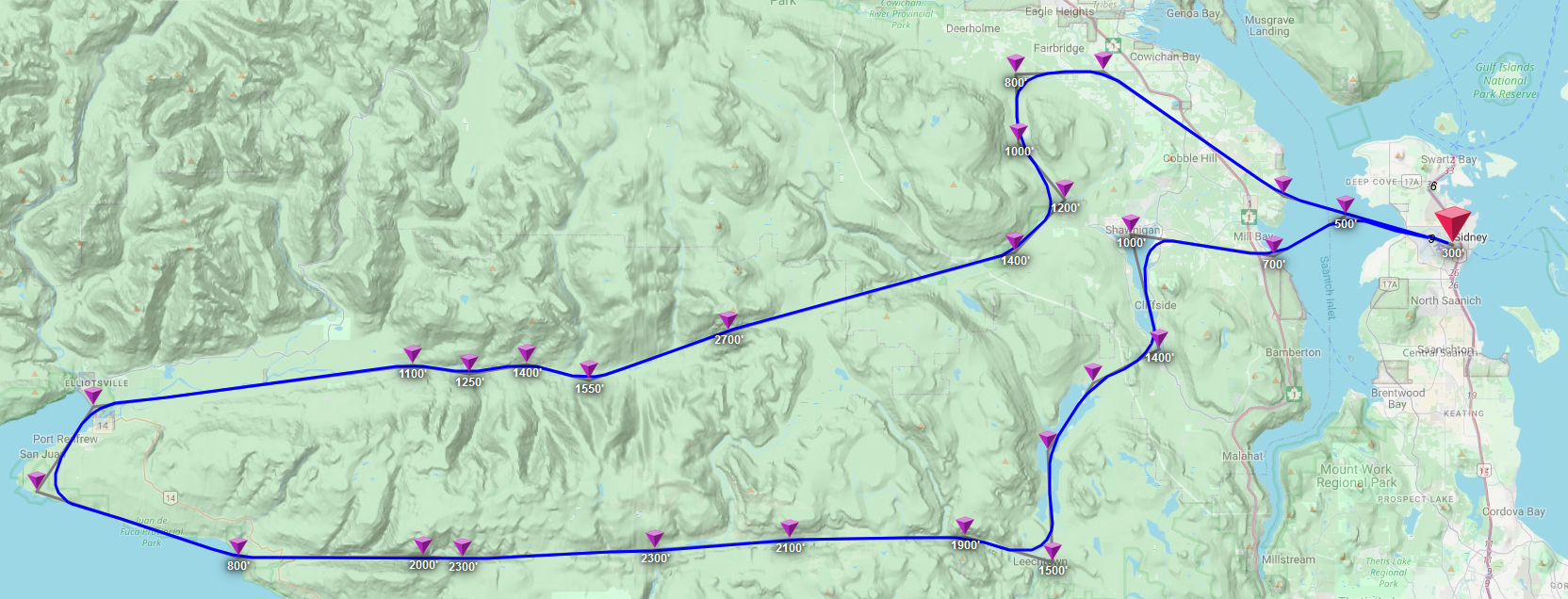

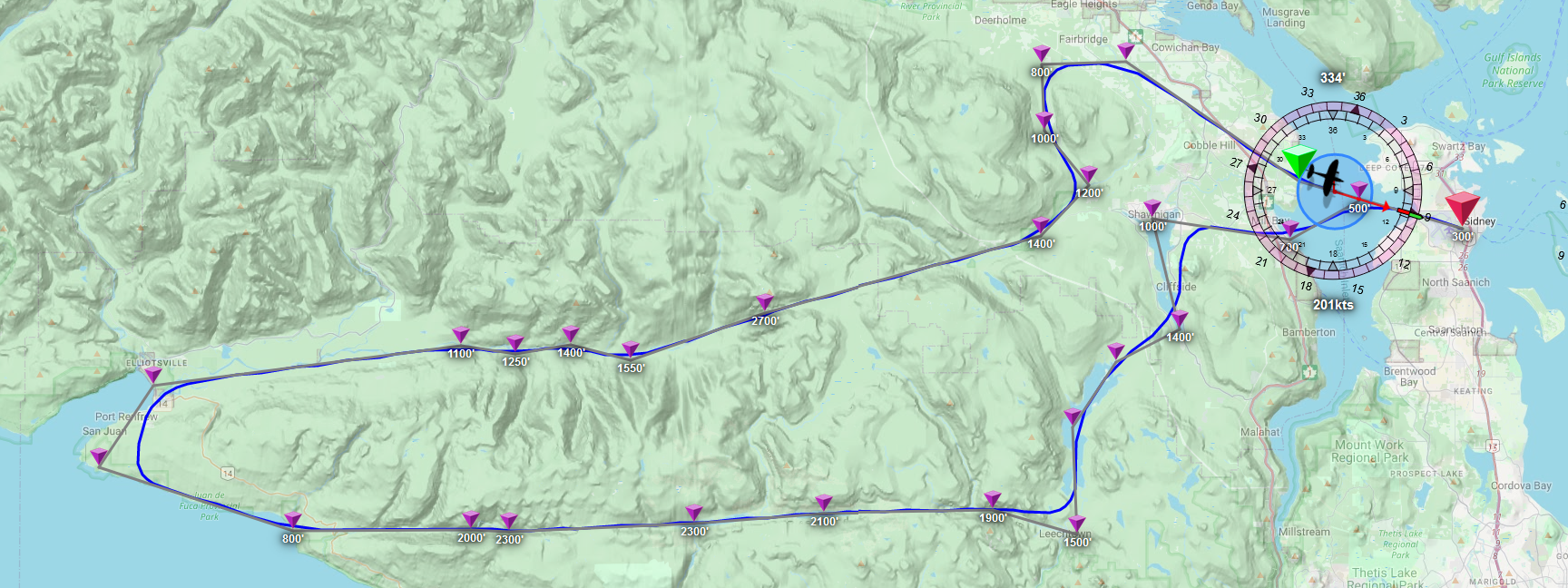

- In the fourth part, we’re going to cover the “flight path” part of a modern autopilot, but rather than programming specific radio beacons and airports, we’re going the google maps route, where you just place markers on the map and then the plane flies the path through those markers.

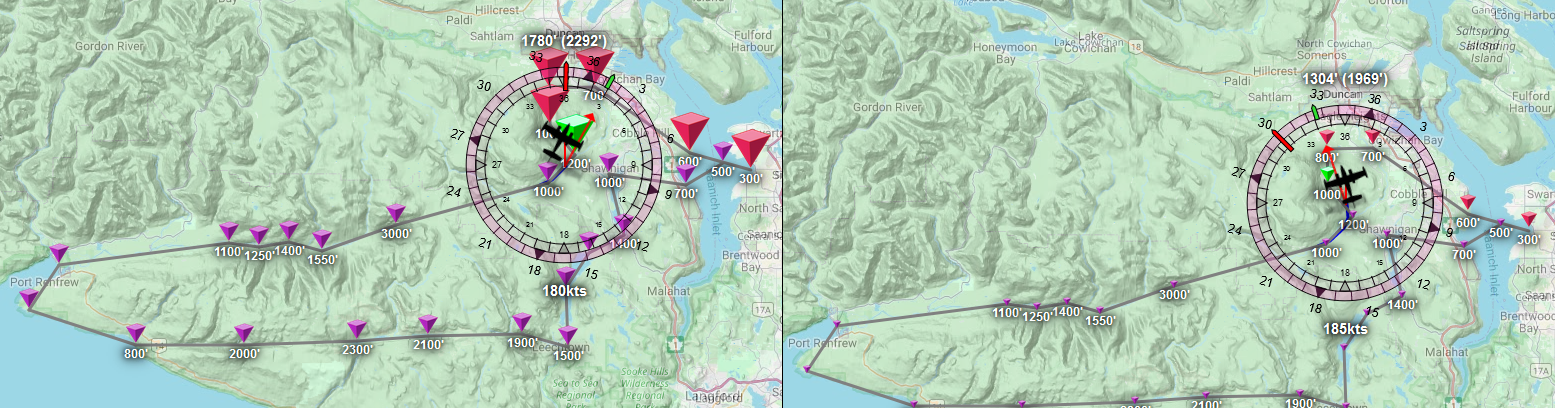

- Part five is dedicated to running test flights and rewriting some of our code based on the flight behaviour of a variety of in-game planes ranging from ultra light to commercial jet airliners.

- In the sixth part, we’re going to cover the thing you didn’t even realize you came here for: literally making JavaScript fly our plane for us, where we spawn a plane on the runway, click “take off” in the browser and have the plane just… start flying in MSFS with us along for the ride, following our flight path with automatic elevation detection, and then when we click “land”, having the autopilot find a nearby airport, figure out an approach, and then land the plane for us. Because we can.

And along the way we’re going to learn a few developer tricks like hot reloading ES modules, mocking SimConnect, and other such fun things.

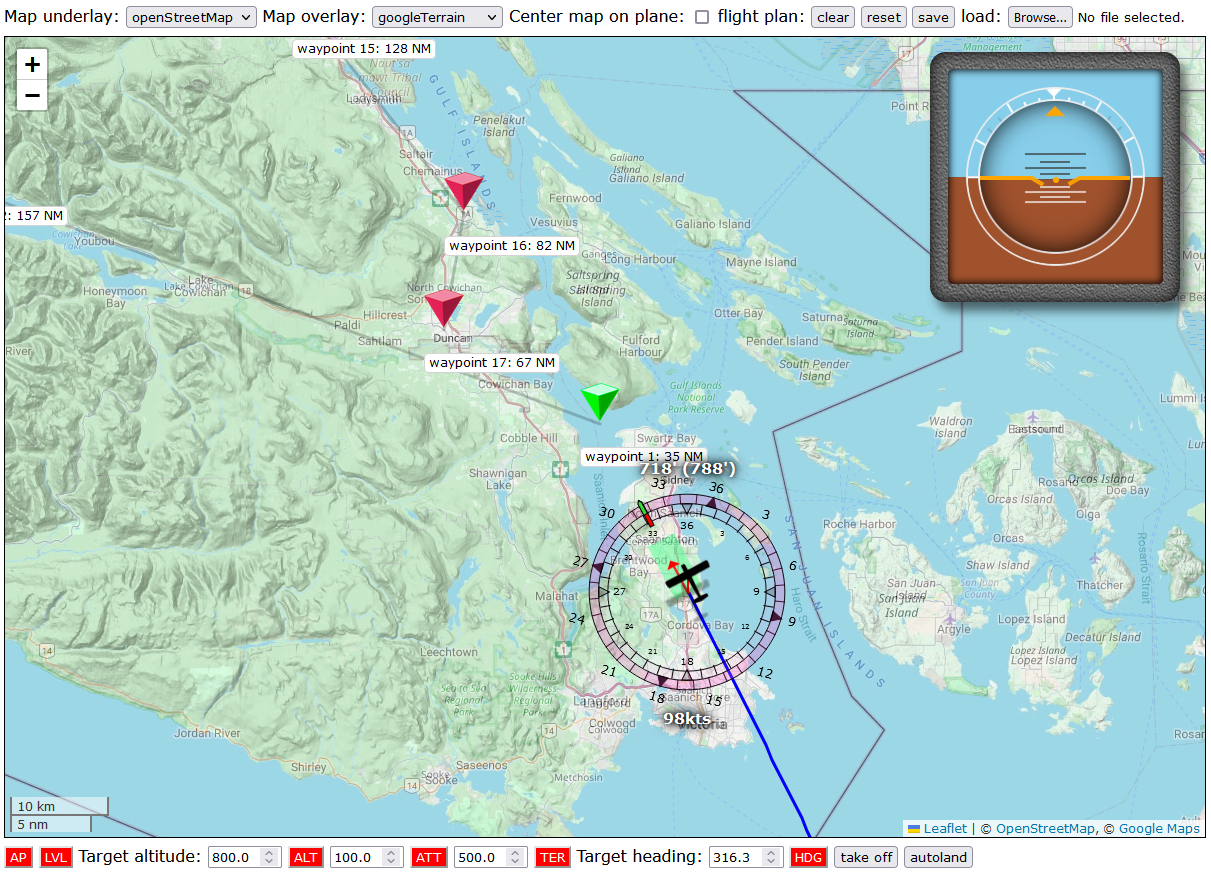

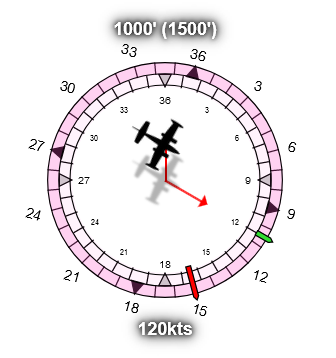

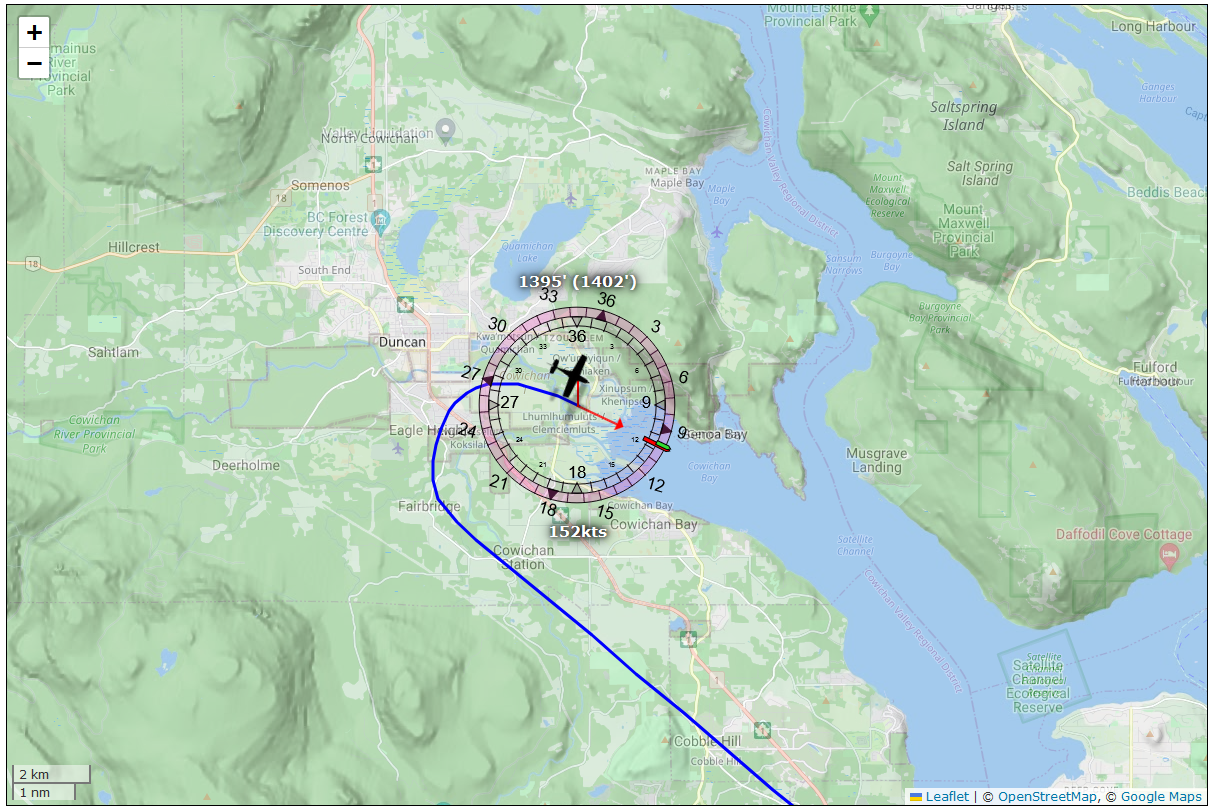

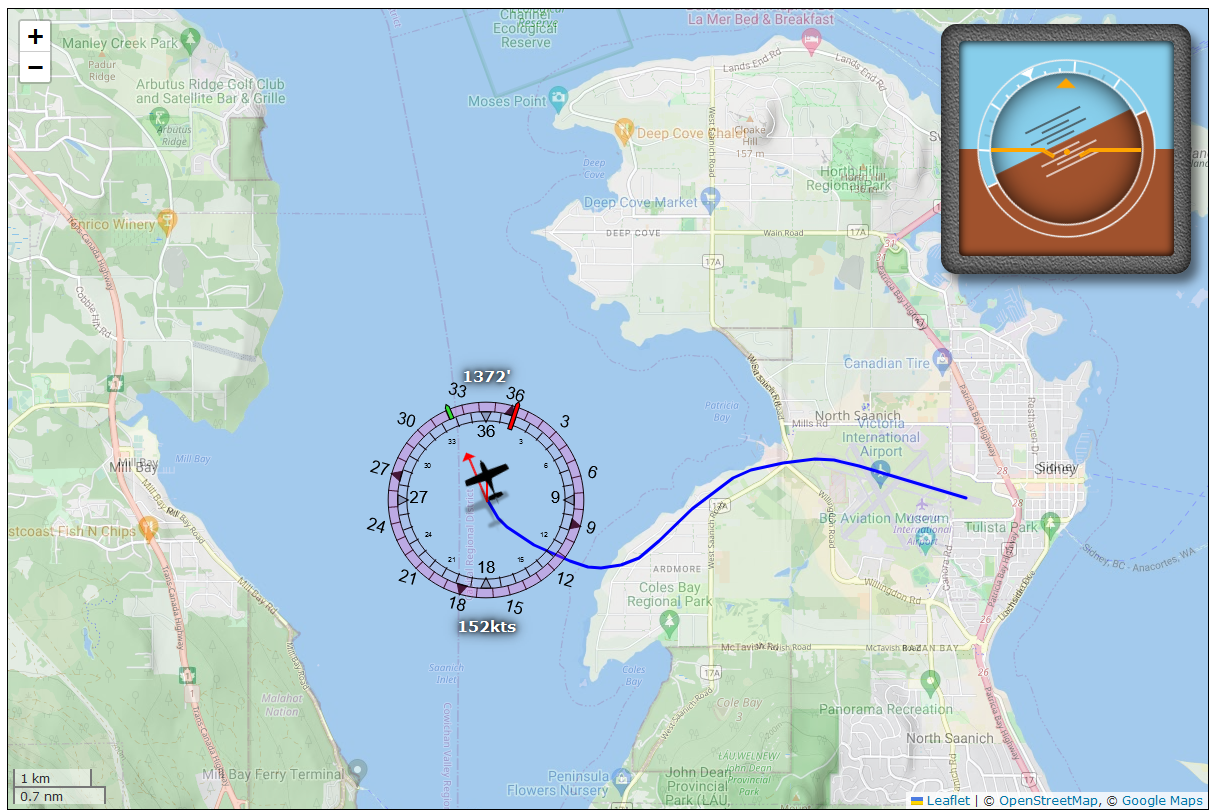

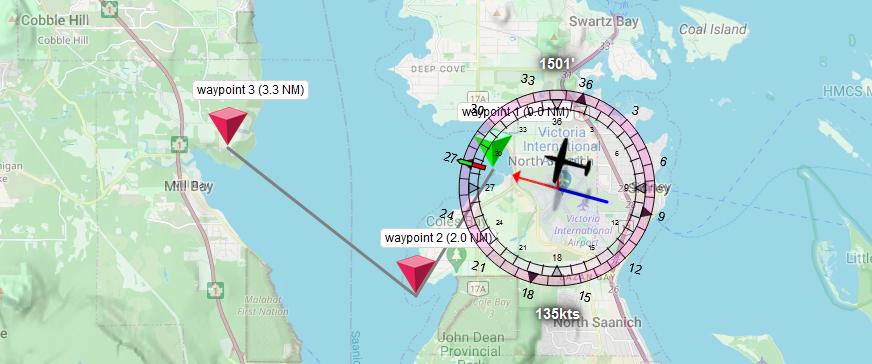

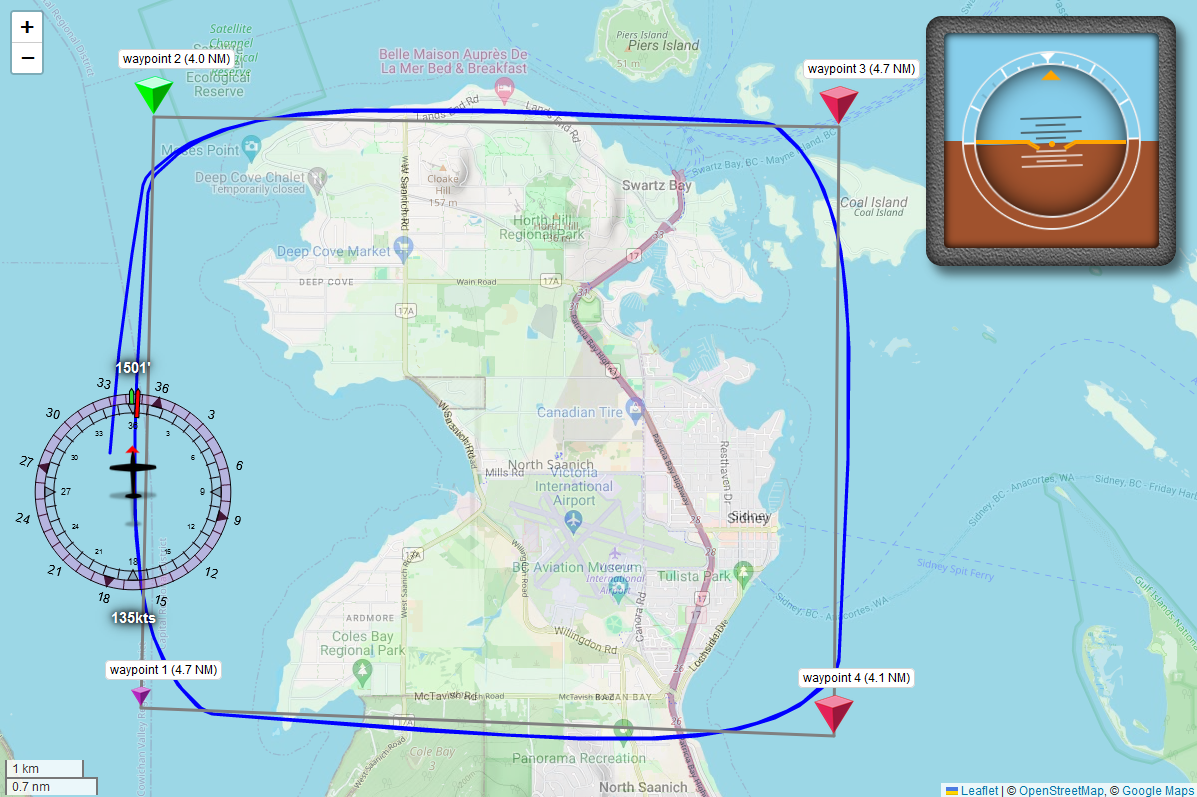

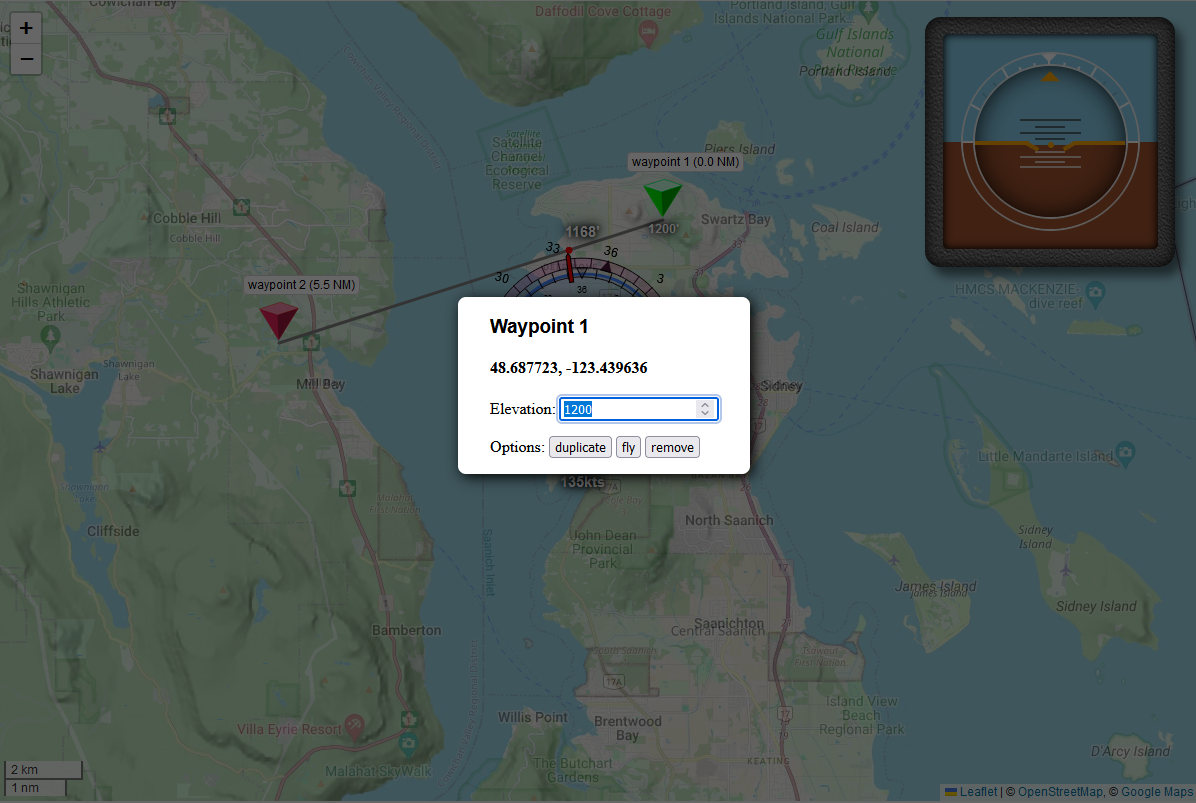

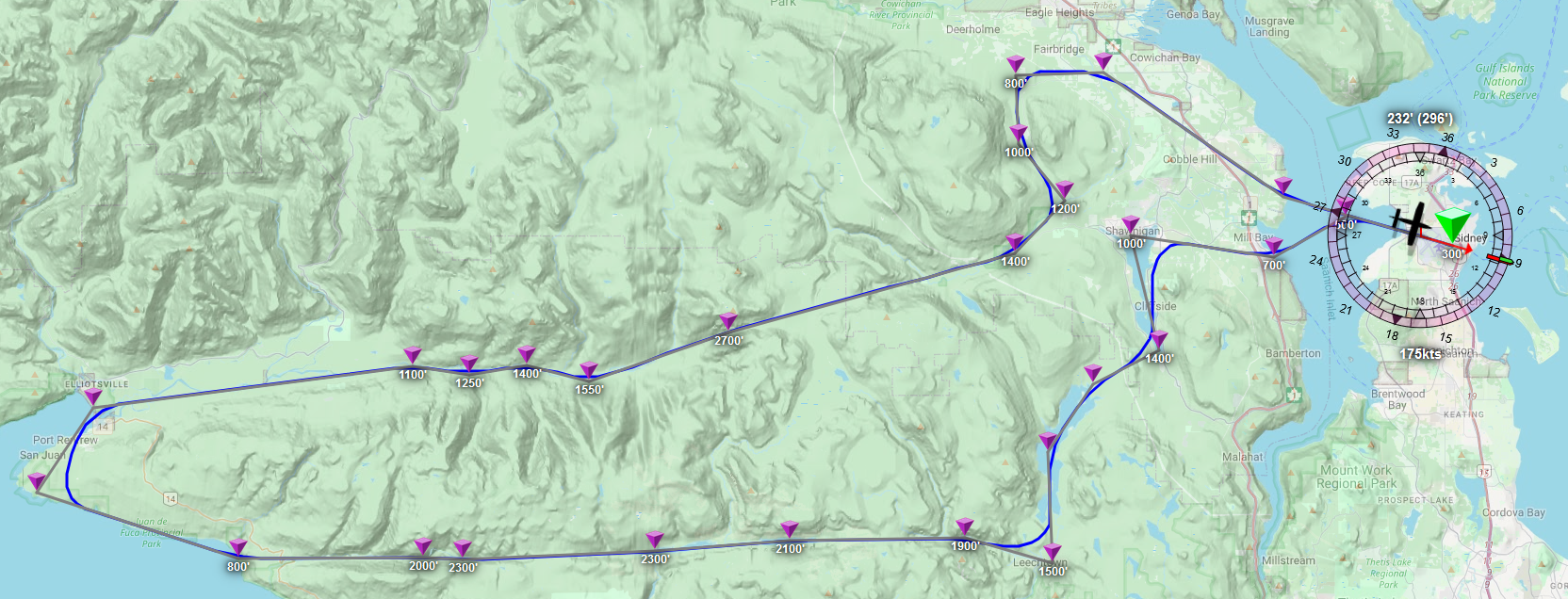

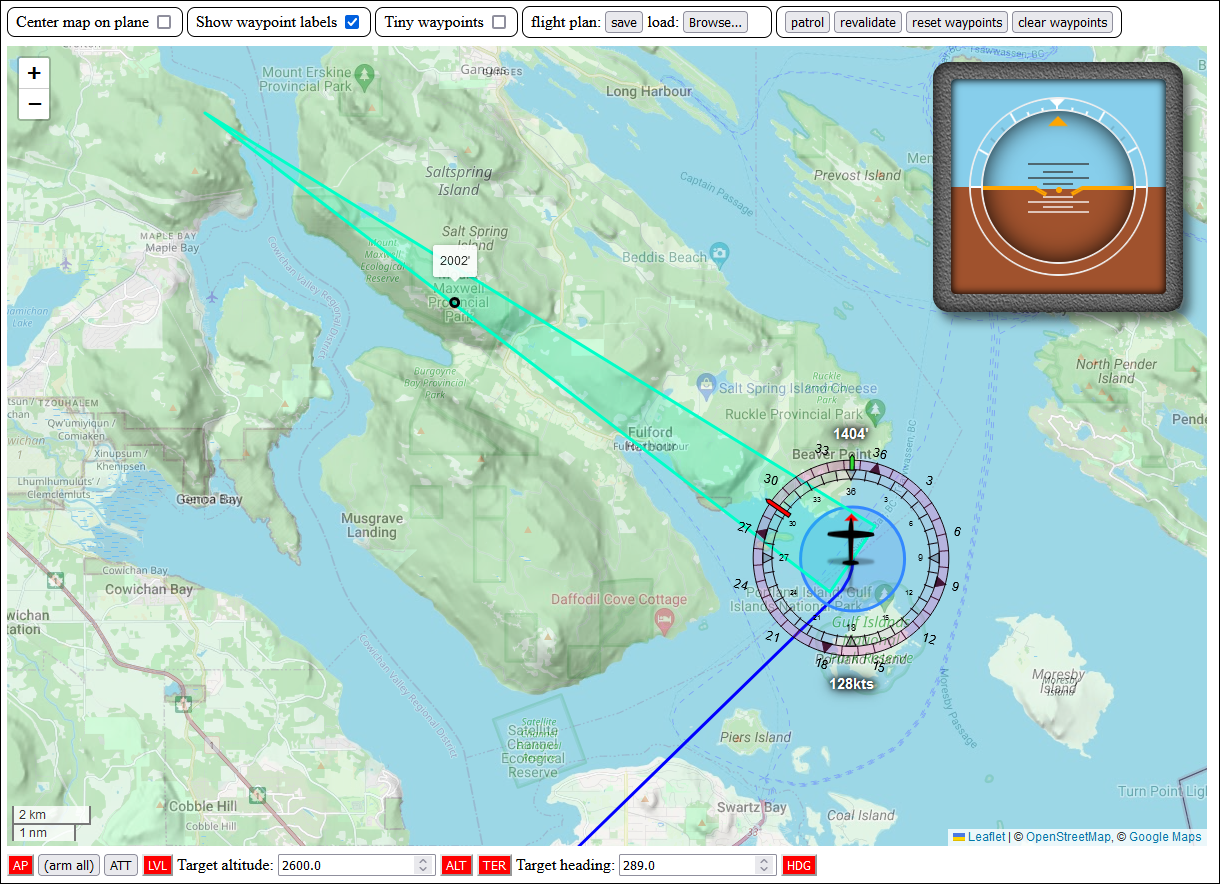

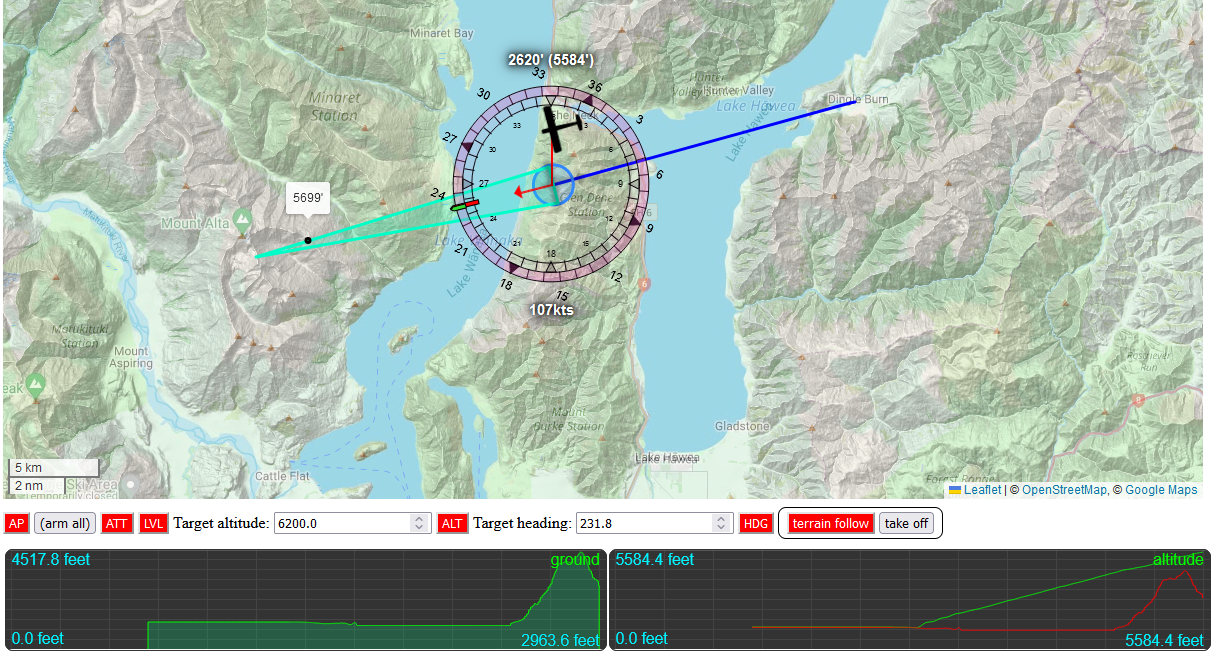

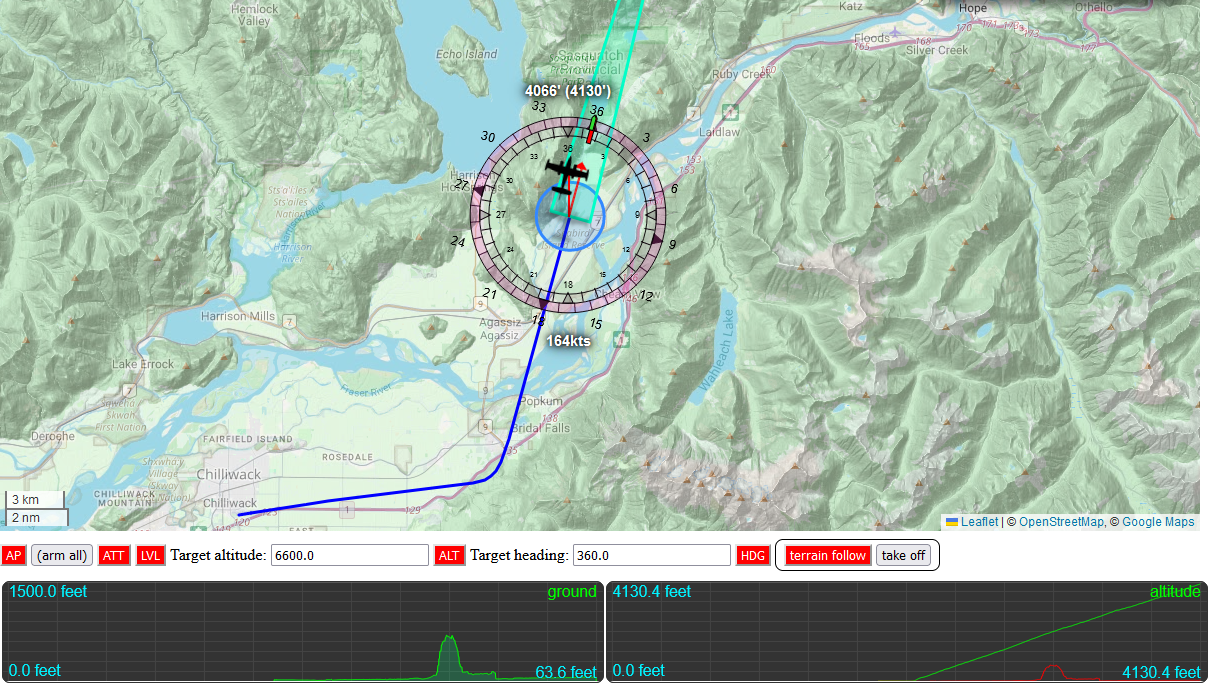

By the time we’re done, we’ll have a web page that looks a little bit like this:

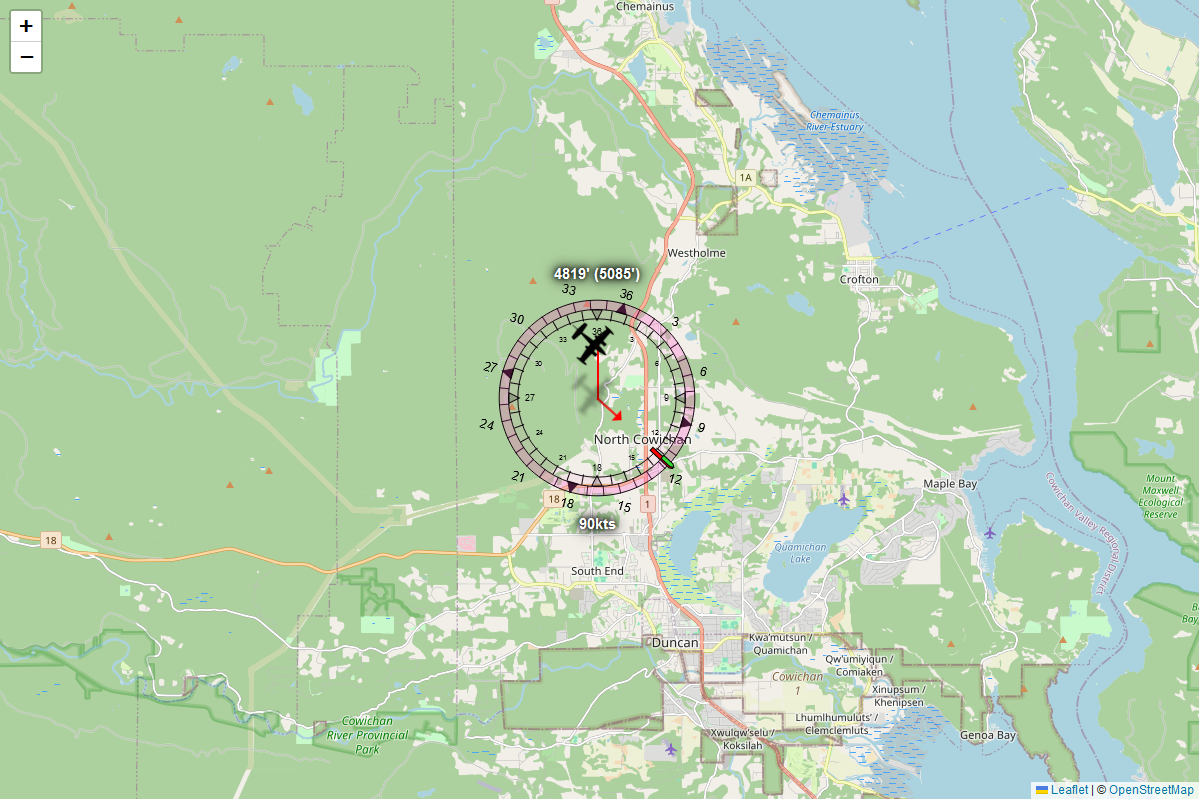

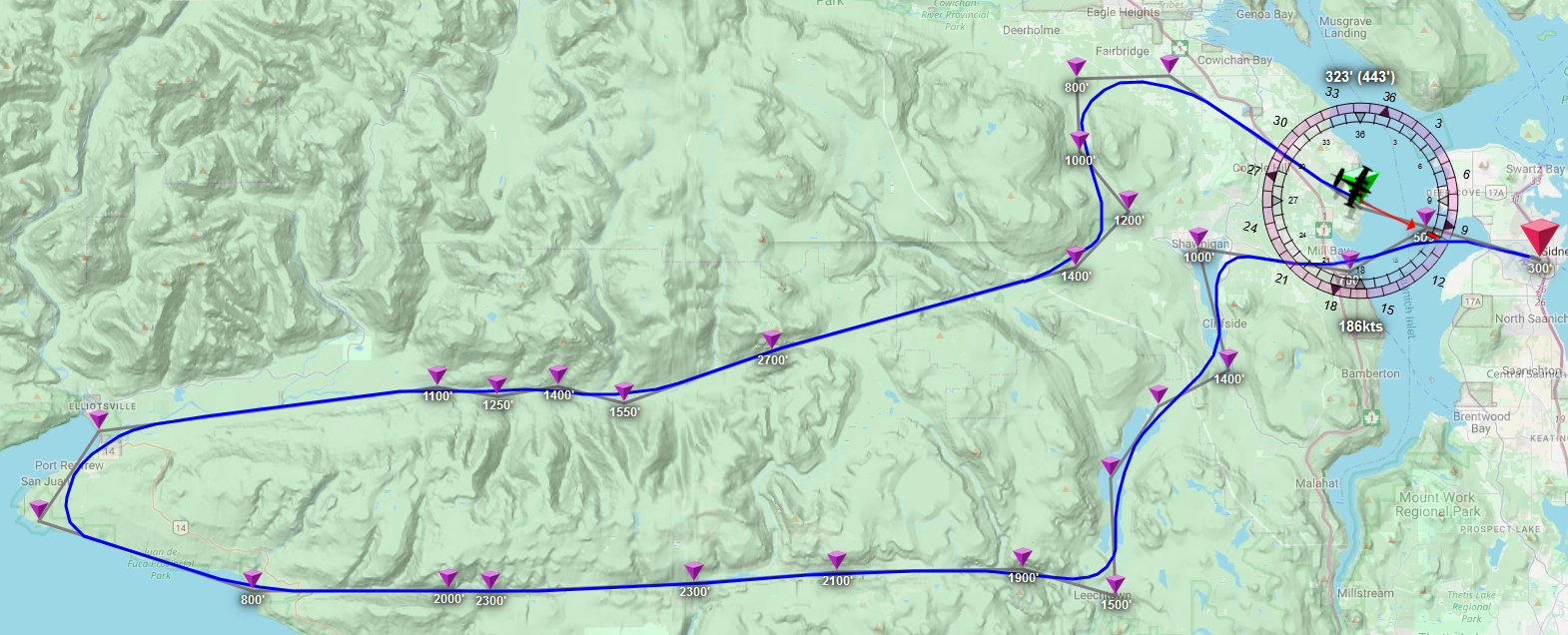

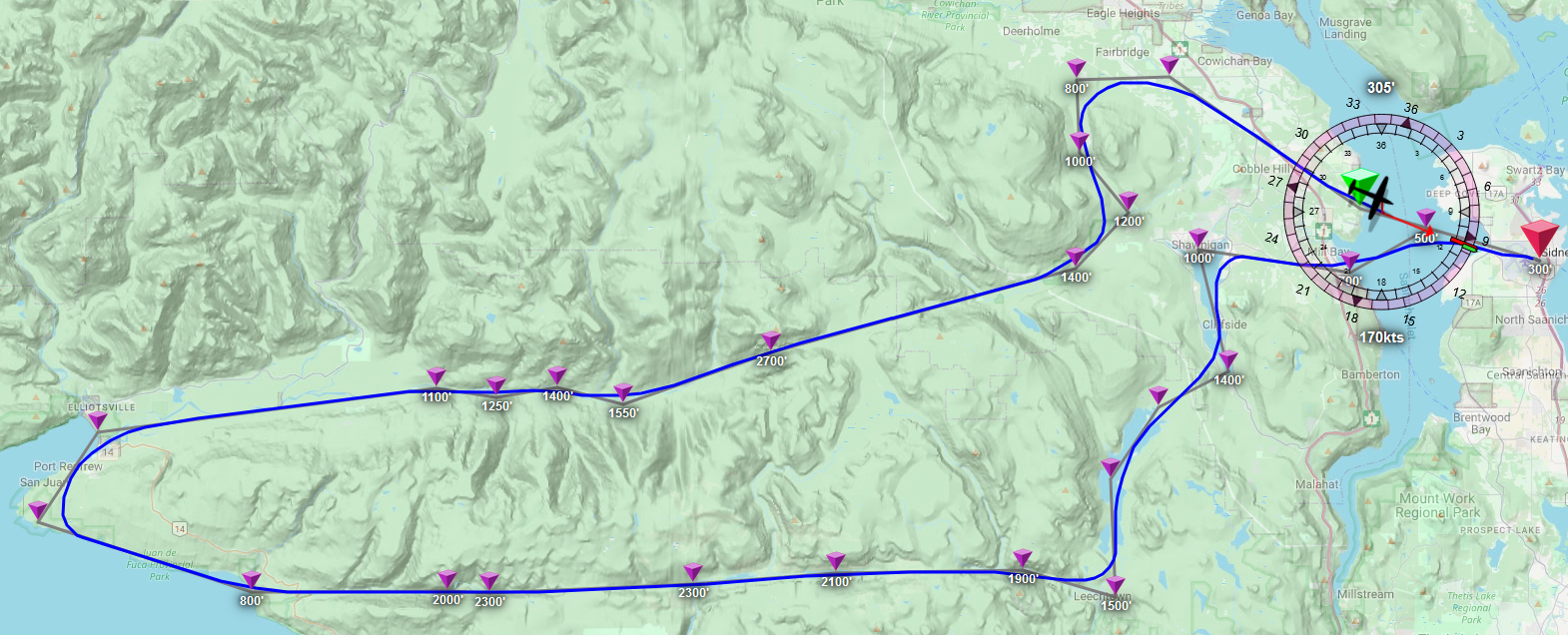

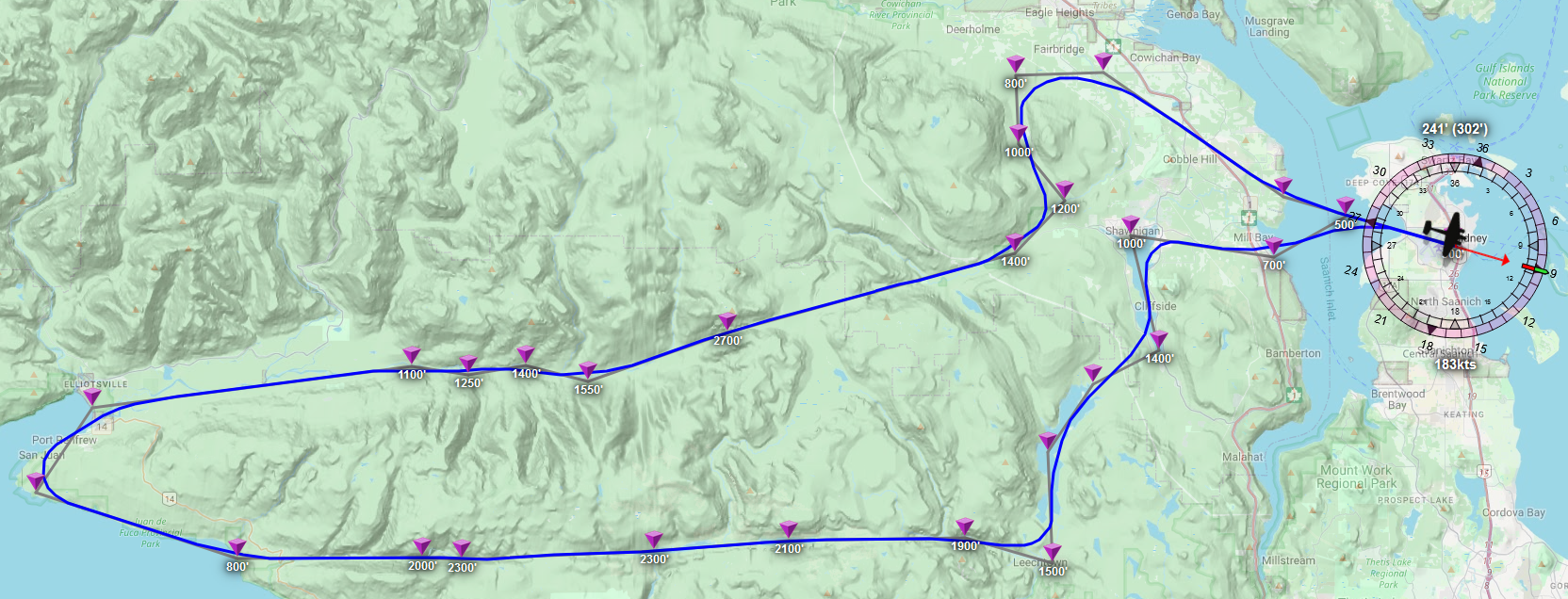

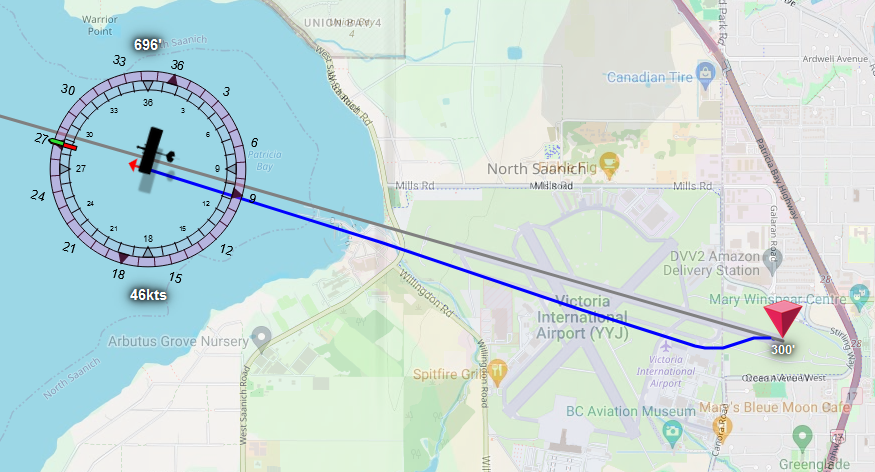

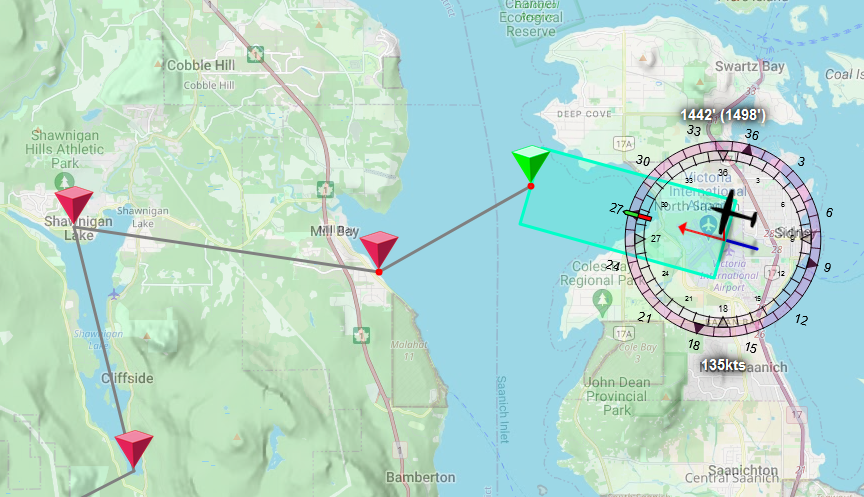

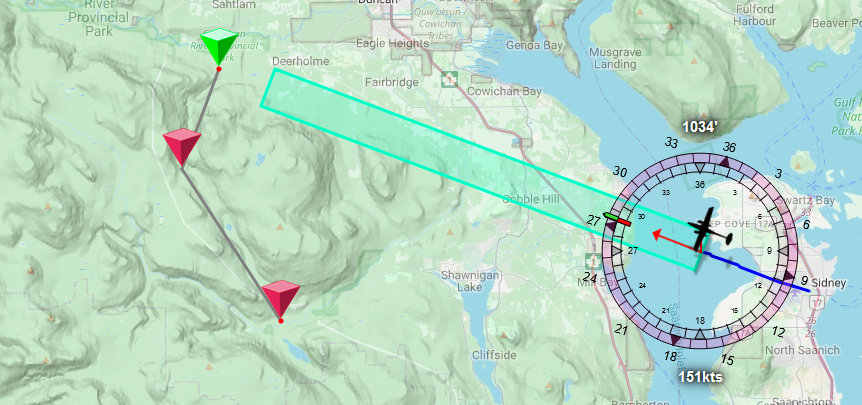

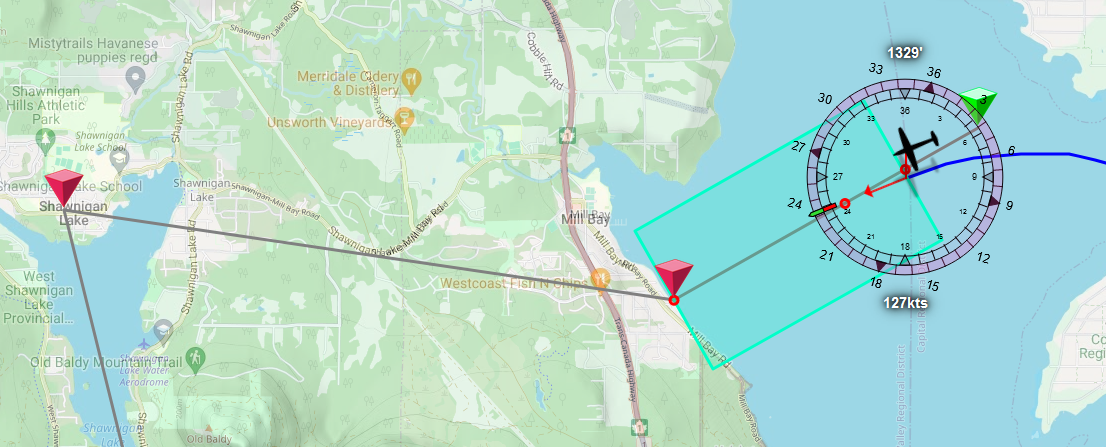

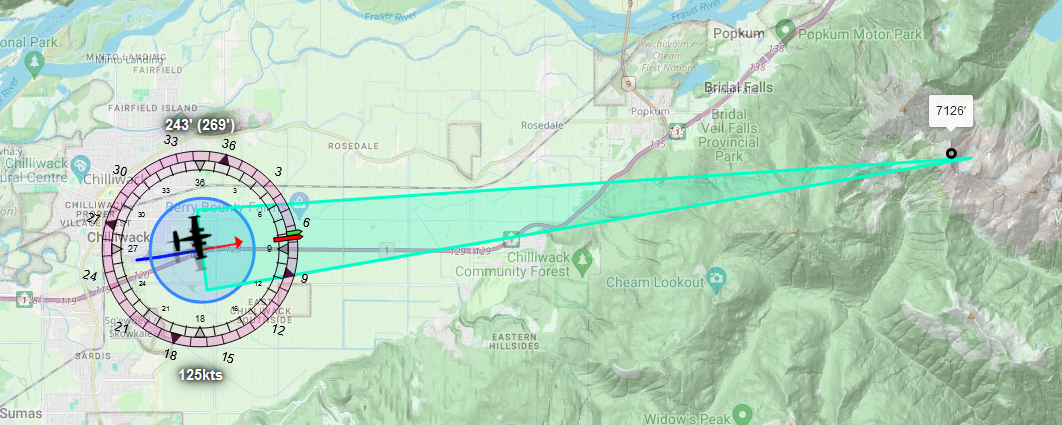

While the in game view looking like this:

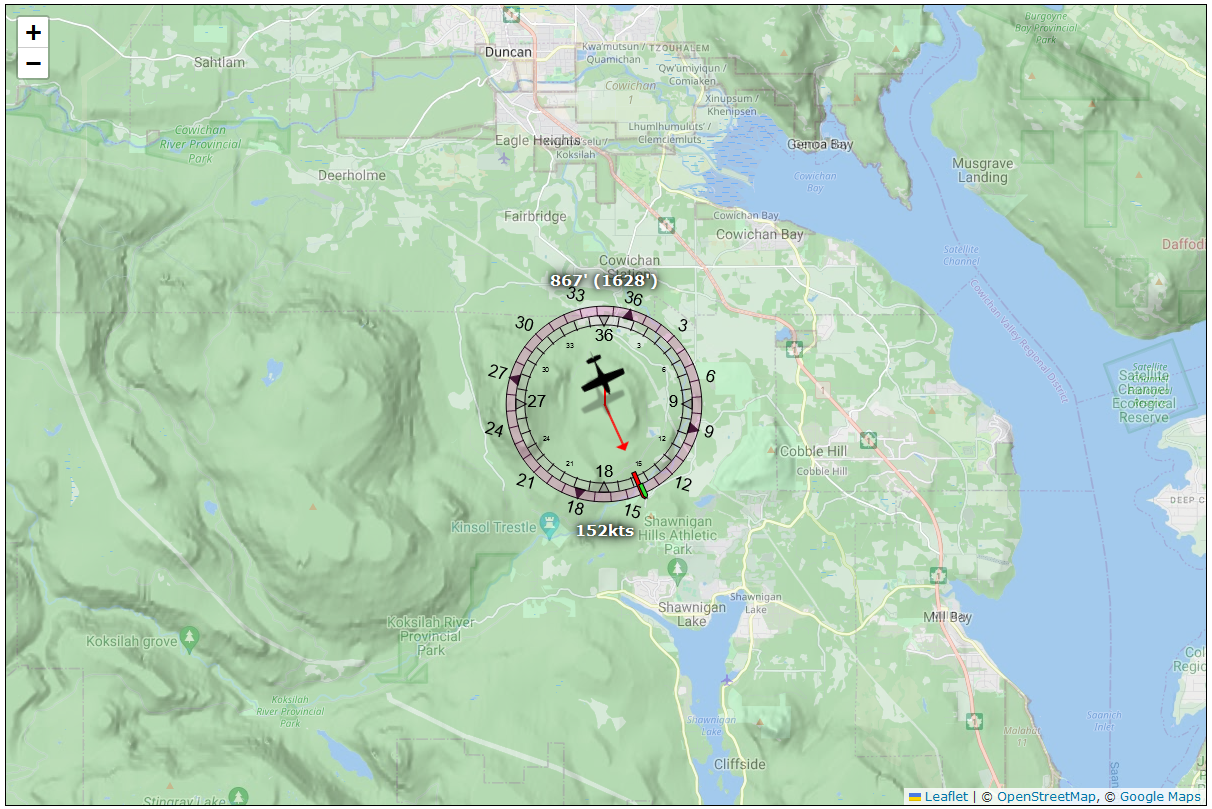

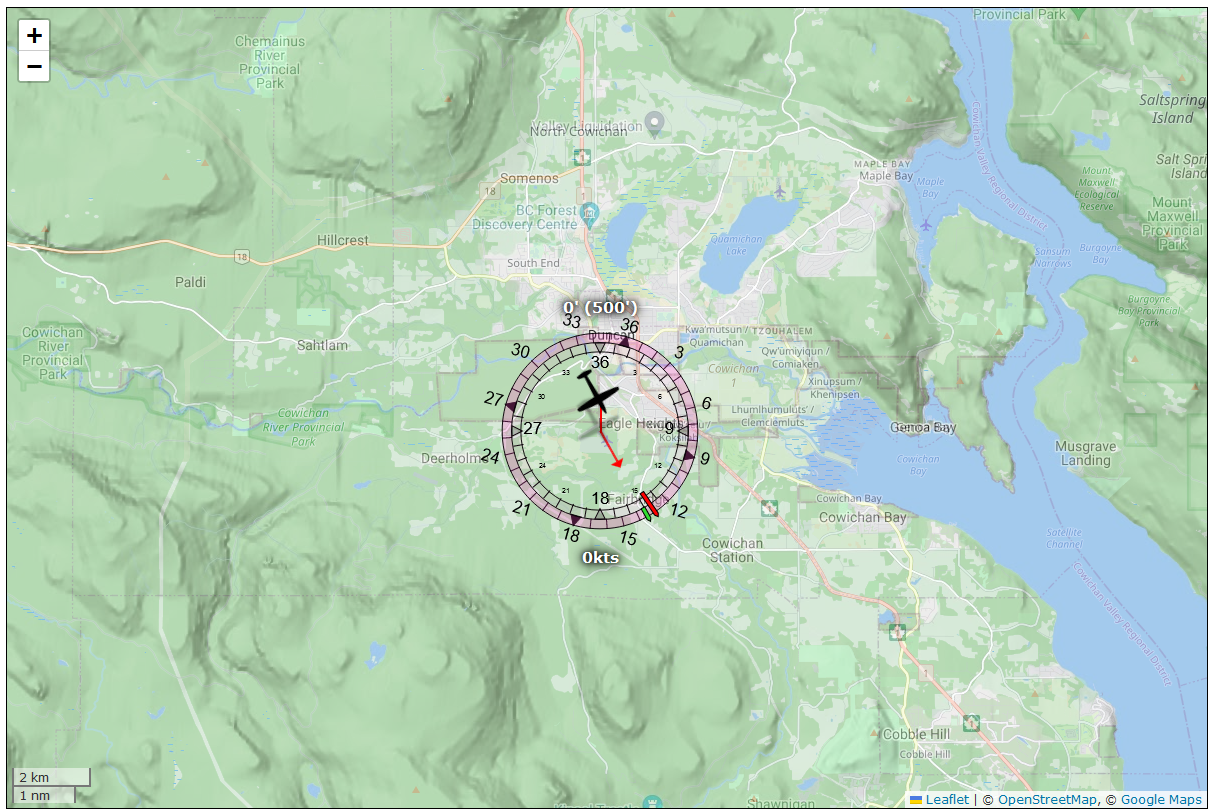

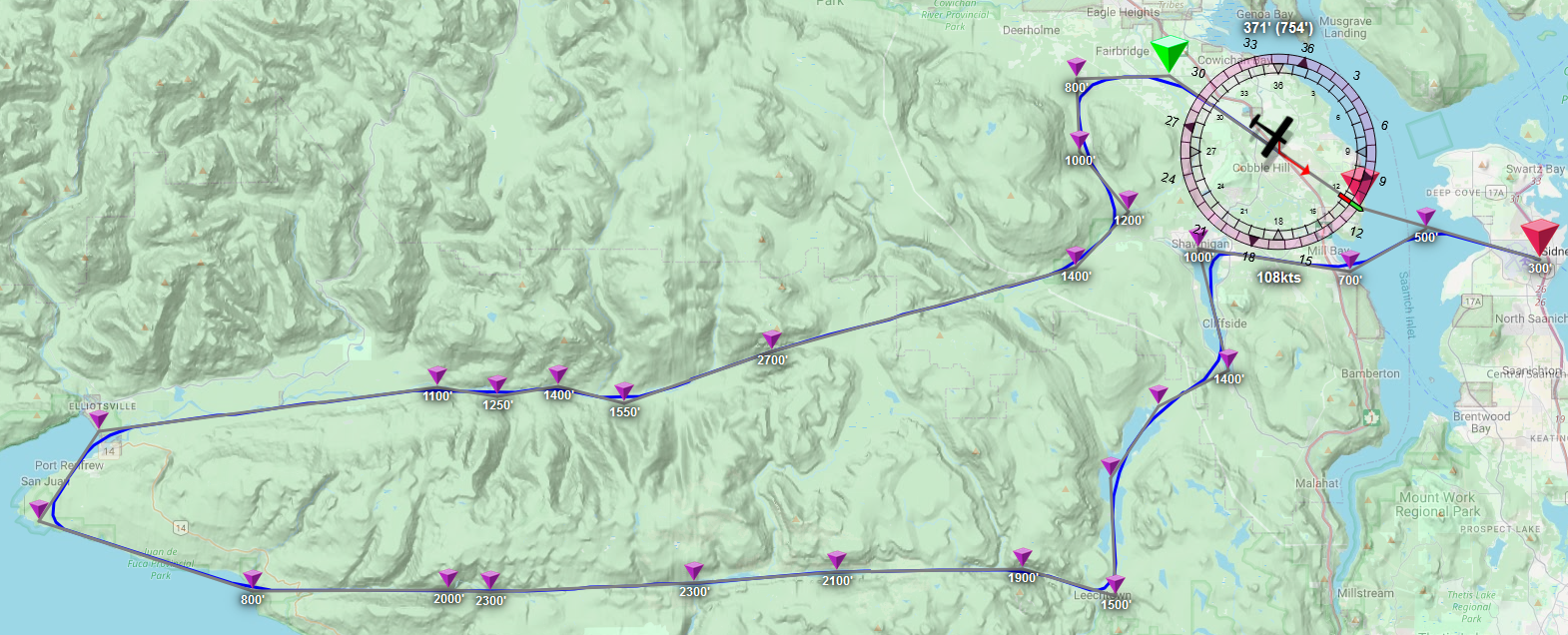

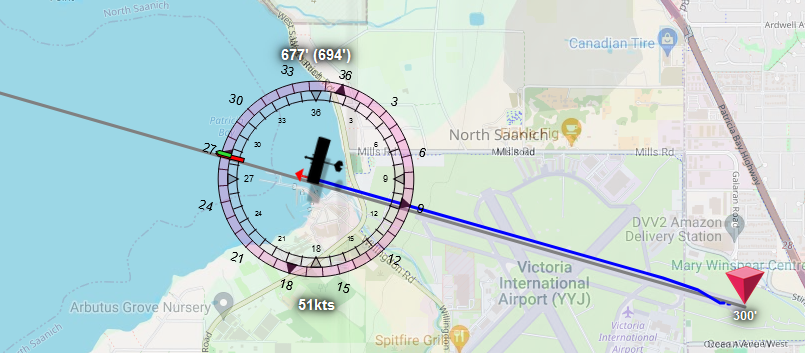

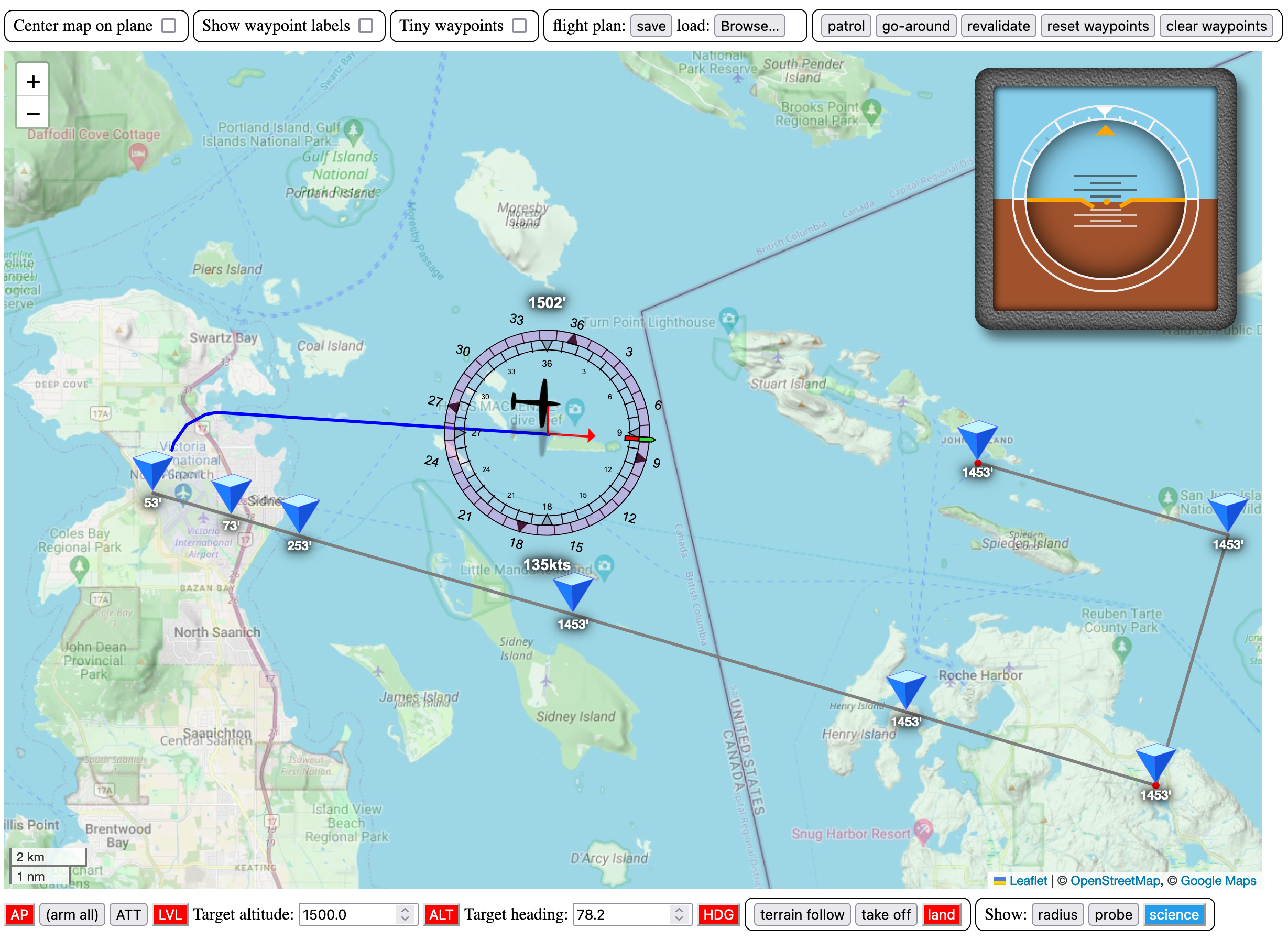

or this:

If that sounds (and looks) good to you, then read on!

Table of Contents

- The structure of this “tutorial”

- Part 1: The prep work

- Part 2: visualizing flights

- Part 3: writing an autopilot

- Part 4: Google maps for planes

- Part 5: Testing and refining our code

- Part 6: “Let’s just have JavaScript fly the plane for us”

- Terrain follow mode

- Auto takeoff

- Auto-landing

- Conclusions

- Questions and comments

Part 1: The prep work

As mentioned, we’re going to have to do a bit of prep work before we can start writing the fun stuff, so let’s get this done. We’re going to implement three things:

- An API server that talks directly to MSFS, and accepts web socket connections that can be used by API clients to interact with MSFS,

- a web server that serves a webpage, and accepts web socket connections from the webpage, which it can forward to the API server, and

- a web page with some code that connects it to the API (as far as it knows) using a web socket and can show the various aspects of a flight.

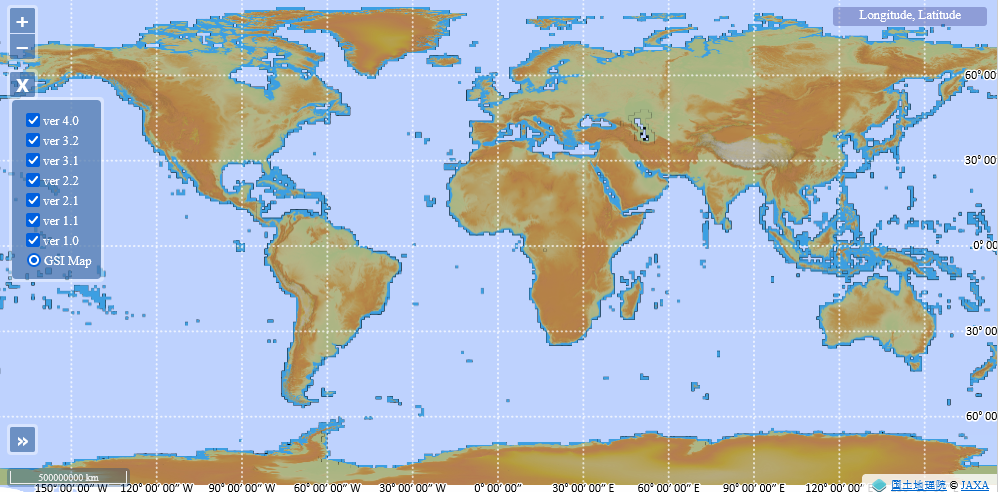

In high fidelity image media, we’ll be implementing this:

And as mentioned, to make our lives a little easier we’re going to be using the socketless library to take care of the actual client/server management, so we can just focus on writing the code that’s going to let us show a user interface based on talking to MSFS. The nice thing about this library is that it does some magic that lets clients and servers call functions on each other “without knowing there’s a network”. If the server has a function called test then the client can just call const testResult = await this.server.test() and done, as far as the client knows, the server is just a local variable. Similarly, if the client has a function called test then server can call that with a const testResult = await this.clients[...].test() and again, as far as the server knows it’s just working with a local variable.

Setting up our project

Let’s start by creating a new dir somewher called are-we-flying and initialising it as a Node project:

> mkdir are-we-flying

> cd are-we-flying

are-we-flying> npm init -y

after which we can install the dependencies that we’ll need: dotenv, open, socketless, and msfs-simconnect-api-wrapper.

> npm i dotenv open socketless msfs-simconnect-api-wrapper

Then, we want to make sure to tell Node that we we’ll be writing normal, modern JS with JS modules, rather than Node’s legacy module system: open package.json and add the key/value pair "type": "module" .

An .env file

Next up, we’ll create a file called .env that will house a few variables that we want to be using across all our code:

WEB_PORT=3000

API_PORT=8080

Nothing fancy, just two port numbers for now.

A “socketless” API, and web servers

Before we look at the “real” code we want to write, let’s quickly run through the “boilerplate” code we need to run our API server, which we’ll put in api-server.js:

// First we load our .env file:

import url from "node:url";

const __dirname = url.fileURLToPath(new URL(".", import.meta.url));

import dotenv from "dotenv";

dotenv.config({ path: `${__dirname}/.env` });

// And get our API server's port from that environment:

const { API_PORT } = process.env;

// Then we set up socketless so it can do its thing:

import { createServer } from "socketless";

import { ServerClass } from "./src/classes/index.js";

// Where "its thing" is creating an API server instance:

const { webserver } = createServer(ServerClass);

// Which we then run like you would any other Node server.

webserver.listen(API_PORT, () => {

console.log(`Server listening on http://localhost:${API_PORT}`);

});

And that’s all the code we need to set up a server (ignoring the actualy ServerClass, which we’ll look at in a bit). So next up is the code required to run the “web server” part of our above diagram, which we’ll put in web-server.js:

// We start the same was as above:

import url from "node:url";

const __dirname = url.fileURLToPath(new URL(".", import.meta.url));

import dotenv from "dotenv";

dotenv.config({ path: `${__dirname}/.env` });

// Instead of "just a server" our web server will act as a client

// to our API server, but as web server for browsers that try to

// connect. As such we need to know both the port for our API server

// as well as what port we should use for our own server:

const { API_PORT, WEB_PORT } = process.env;

// Then we set up a socketless client with "browser connection" functionality:

import { ClientClass } from "./src/classes/index.js";

import { createWebClient } from "socketless";

// Clients need to know which URL to find the server at:

const serverURL = `http://localhost:${API_PORT}`;

// And web clients need to know which directory/folder to serve static content from:

const dir = `${__dirname}/public`;

// Which means we can now create our "web-enabled client":

const { clientWebServer } = createWebClient(ClientClass, serverURL, dir);

// And then we run its web server the same way we ran the API server:

clientWebServer.listen(WEB_PORT, () => {

console.log(`Server listening on http://localhost:${WEB_PORT}`);

// With an extra bit that automatically opens a browser for us:

if (process.argv.includes(`--browser`)) {

import("open").then(({ default: open }) => {

open(`http://localhost:${WEB_PORT}`);

});

}

});

So a tiny bit more code, but that’s all we need to do in terms of setting up our “API server ↔ client ↔ browser” constellation. The socketless library takes care of all of that so we can focus on actually implementing the code we care about. And on that note, let’s look at that code because we have two classes to implement:

- the server class, which will be our interface between MSFS and our clients, and

- the client class, which will be our interface between the server and the browser.

But first, some testing!

Before we implement those though, let’s verify that the code we wrote even works by implementing some tiny client and server classes with just enough code to show connections and function calls to work. Let’s create a src/classes/index.js with “dummy” client and server classes:

// Our client class will announce its own connection, as well as browser connections:

export class ClientClass {

// nothing special going on here, just a console log

onConnect() {

console.log(`[client] We connected to the server!`);

}

// and nothing special going on here either, just more console log

onBrowserConnect() {

console.log(`[client] A browser connected!`);

}

}

// Our server class will also announce that it got client connections:

export class ServerClass {

// still nothing special going on here...

onConnect(client) {

console.log(`[server] A client connected!`);

}

// ...but we do add a little test function that clients can call:

async test() {

console.log(`[server] test!`);

return "success!";

}

}

Then, to add the browser into the mix, we’ll also create a quick public/index.html file:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en-GB">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<title>Let's test our connections!</title>

<script src="js/index.js" type="module" async></script>

</head>

<body>

<!-- we only need to look at the developer tools "console" tab for now -->

</body>

</html>

And then a bare minimum amount of browser JS in public/js/index.js:

// We don't need to put a "socketless.js" in our public dir,

// this is a "magic import" that works when we're connected

// to a socketless web server:

import { createBrowserClient } from "../socketless.js";

// Then we set up our browser client to announce its connections:

class BrowserClient {

async init() {

console.log(`[browser] We're connected to our web client!`);

// And then as part of startup, we'll call the server's

// test function, just to confirm that works:

console.log(`Calling test:`, await this.server.test());

}

}

// Then the only thing left to do in the browser is to create a browser client instance:

createBrowserClient(BrowserClient);

And that’s it, we just implemented a full server + client + browser constellation!

So let’s run node api-server.js in a terminal, and node web-server.js --browser in another. Doing so will show us the following text in the server terminal:

...> node api-server.js

Server listening on http://localhost:8080

[server] A client connected!

[server] test!

And will show us the following in the client terminal:

...> node web-server.js --browser

Server listening on http://localhost:3000

Opening a browser...

[client] We connected to the server!

[client] A browser connected!

And, because the --browser flag opened a browser, if we look at the browser’s developer tools’ console tab, we see:

[browser] We're connected to our web client! index.js:9:17

Calling test: success!

Awesome, we have a complete API server + web server + browser thin client and “things just work™”, we didn’t have to write a single line of websocket or remote function calling code!

Our API server

Let’s finish up the basics.

Our server is where we “talk to MSFS”, and any functions that we expose on the server class will end up being a function that, as far as clients know, is just part of their local this.server object, so we’ll want to make sure to keep things that should not be directly accessible to clients either out of the serverclass (i.e. declare and initialize them in module scope instead) or mark them as private using the # character, so that they can’t be called by anyone else.

With that in mind, let’s write a real server clas, in its own src/classes/server/server.js file instead, so we’re not mixing client and server code:

// Load the environment:

import url from "node:url";

const __dirname = url.fileURLToPath(new URL(".", import.meta.url));

import dotenv from "dotenv";

dotenv.config({ path: `${__dirname}/../../../.env` });

// And get the "how frequentlu to poll" from theÏ environment.

const POLLING_INTERVAL = process.env.POLLING_INTERVAL ?? 2500;

// Then, an import for a setTimeout that ignores throws:

import { runLater } from "../../utils/utils.js";

// And two helper functions for setting up the API connection:

import { connectServerToAPI, registerWithAPI } from "./helpers.js";

// Plus a helper that we can expose as `this.api` for clients to work with:

import { APIRouter } from "./routers/api-router.js";

// And then the most important import: the MSFS connector

import { MSFS_API } from "msfs-simconnect-api-wrapper";

// In order to prevent clients from directly accessing the MSFS

// connector, we're going to make it a global (to our module):

let api = false;

// Next up, our server class:

export class ServerClass {

async init() {

const { clients } = this;

// set up the API variable - note that because this is a global,

// clients can't directly access the API. However, we'll be setting

// up some API routing to make that a non-issue in a bit.

api = new MSFS_API();

// Set up call handling for API calls: this will be explained after we

// finish writing this class. We bind it as `this.api` so that any

// client will be able to call `this.server.api...` and have things work.

this.api = new APIRouter(api);

// Then wait for MSFS to come online

connectServerToAPI(api, async () => {

console.log(`Connected to MSFS.`);

registerWithAPI(clients, api);

clients.forEach((client) => client.onMSFS(true));

// And when it's online and we're connected, start polling for when we're "in game".

(async function poll() {

// We'll look at what actually goes here once we have everything in place.

// For now, we just schedule a poll

runLater(poll, POLLING_INTERVAL);

})();

});

}

/**

* Then a minimum amount of code for When a client connects to us,

* and MSFS is already connected.

*/

async onConnect(client) {

if (api?.connected) client.onMSFS(true);

}

}

So let’s look at those secondary imports: first, the simplest one, in src/utils/utils.js:

export function runLater(fn, timeoutInMillis) {

// this is literally just setTimeout, but with a try/catch so

// that if the function we're running throws an error, we

// completely ignore that instead of crashing the server.

setTimeout(() => {

try {

fn();

} catch (e) {

console.error(e);

}

}, timeoutInMillis);

}

Then those helper functions for working with the API in src/classes/server/helpers.js

// We'll grab the list of system events from the MSFS connector, so we can register for a few events:

import { SystemEvents } from "msfs-simconnect-api-wrapper";

// Then mostly for organizational purposes ("to keep the code clean")

// we house the actually MSFS API connection properties here.

export function connectServerToAPI(api, onConnect) {

api.connect({

autoReconnect: true,

retries: Infinity,

retryInterval: 5,

onConnect,

onRetry: (_, s) =>

console.log(`Can't connect to MSFS, retrying in ${s} seconds`),

});

}

// And since this is basically a "run once" thing we also house the code

// that registers for pause and crash events here.

export function registerWithAPI(clients, api) {

console.log(`Registering API server to the general sim events.`);

api.on(SystemEvents.PAUSED, () => {

clients.forEach((client) => client.pause());

});

api.on(SystemEvents.UNPAUSED, () => {

clients.forEach((client) => client.unpause());

});

api.on(SystemEvents.CRASHED, () => {

clients.forEach((client) => client.crashed());

});

api.on(SystemEvents.CRASH_RESET, () => {

clients.forEach((client) => client.crashReset());

});

}

Which leaves the code that lets clients call API functions through the server

The API Router

The APIRouter code lets clients interface “directly” with MSFS through the SimConnect driver, with five main functions that we can expose to clients:

- register: register as event listener for one of the (few) “subscription” based MSFS event.

- forget: the opposite of register.

- get: a way to get the current value(s) for SimConnect variable(s).

- set: a way to set variable(s) to specific value(s).

- trigger: a way to trigger one of the (many) sim events.

So let’s look at how we expose those to the client in a file that we’ll call src/classes/routes/api-router.js:

// Obviously we'll need to load the list of events if we're going to let clients register for events:

import { SystemEvents } from "msfs-simconnect-api-wrapper";

const eventTracker = {};

// And in order to cache GET requests, we're going to hash requests based on

// the varname collection we get passed, which we'll do by hashing.

import { createHash } from "node:crypto";

const resultCache = {};

// Since there is only one API instance, we can cache that

// at the module level, just like in the server class.

let api;

export class APIRouter {

// And then we bind that variable using the constructor:

constructor(_api) {

api = _api;

}

// Then, when clients call this.server.register(...), we:

async register(client, ...eventNames) {

if (!api.connected) return;

eventNames.forEach((eventName) => this.#registerEvent(client, eventName));

}

// With a private function for registering events on the API:

#registerEvent(client, eventName) {

const tracker = (eventTracker[eventName] ??= { listeners: [] });

// One that can response to custom "api server only" event requests:

if (eventName === `MSFS`) {

return client.onMSFS(api.connected);

}

// And has additional logic for making sure a client doesn't "double-register":

if (tracker.listeners.includes(client)) {

console.log(

`Ignoring ${eventName} registration: client already registered. Current value: ${tracker.value}`

);

return false;

}

// When a client registers for a sim event like "SIM" or "FLIGHT_LOADED",

// we assume we can call them back with event information on function

// names like onSim and onFlightLoaded:

const eventHandlerName =

`on` +

eventName

.split(`_`)

.map((v) => v[0].toUpperCase() + v.substring(1).toLowerCase())

.join(``);

// So: ask the API to register for this event, with an appropriate

// bit of code to handle "what to do when SimConnect flags this event".

if (!tracker.off) {

tracker.off = api.on(SystemEvents[eventName], (...result) => {

tracker.value = result;

tracker.listeners.forEach((client) =>

client[eventHandlerName](tracker.value)

);

});

}

}

// And when clients call this.server.forget(...), we do the opposite:

async forget(client, eventName) {

if (!api.connected) return;

const pos = eventTracker[eventName].listeners.findIndex(

(c) => c === client

);

if (pos === -1) return;

eventTracker[eventName].listeners.splice(pos, 1);

if (eventTracker[eventName].listeners.length === 0) {

eventTracker[eventName].off();

}

}

// And when clients call this.server.get(...), we cache the set of simvars

// that are being requested, so we don't ask SimConnect for the same data

// several times, if several clients want the same information at the same time.

async get(client, ...simVarNames) {

if (!api.connected) return {};

const now = Date.now();

const key = createHash("sha1").update(simVarNames.join(`,`)).digest("hex");

// assign a new expiry, if there is no cached entry already:

resultCache[key] ??= { expires: now };

// did our cached entry "expire"? (which, if we just made it, won't be the case of course)

if (resultCache[key]?.expires <= now === true) {

resultCache[key].expires = now + 100; // ms

// we cache a promise, rather than data, so we can "await"

resultCache[key].data = new Promise(async (resolve) => {

try {

resolve(await api.get(...simVarNames));

} catch (e) {

// Also make sure to never crash the server if there's a problem with a simvar:

console.warn(e);

resolve({});

}

});

}

// And then we await the cache entry's data before responding. If this is a

// request for data that was previously cached already, then this will pretty

// much resolve instantly. Otherwise, it'll resolve once we get data from the API.

return await resultCache[key].data;

}

// when clients call this.server.set(...), we forward that to the API:

async set(client, simVars) {

if (!api.connected) return false;

if (typeof simVars !== `object`)

throw new Error(`api.set input must be an object.`);

// But we make sure to handle each setter separately, so we can

// report any and all errors, without breaking the entire call.

const errors = [];

const entries = Object.entries(simVars);

entries.forEach(([key, value]) => {

try {

api.set(key, value);

} catch (e) {

errors.push(e.message);

}

});

return errors.length ? errors : true;

}

// And for triggers, we forward those too, but we only allow single triggers per call.Ï

async trigger(client, eventName, value) {

if (!api.connected) return false;

api.trigger(eventName, value);

}

}

Phew. That was a lot of code! But hopefully, it all made sense. Because we still have to look at our client class… which is going to be a lot less code =)

Our browser-connection-accepting client

In addition to our API server, we’re going to need a client that is also a web server, so that we can connect a browser and actually, you know, use all of this. This means we’ll have to define a client class such that socketless can take care of the rest. Thankfully, this is super easy: our client doesn’t need to “do” anything other than make sure that values make it from the server to the browser, and vice versa, so we’re going to essentially be writing a state-manager, where the client takes signals from the server and turns them into updates to its this.state variable, and then socketless will take care of the tedious “making sure the browser gets that” parts. So: client class time! (which we put in its own src/classes/client.js)

import { runLater } from "../../utils/utils.js";

// when we lose the connection to the server, this will be our reconnection interval:

const RECONNECT_TIMEOUT_IN_MS = 5000;

// A timeer variable for when we need to (re)try (re)connecting.

let reconnection;

/**

* Our client class

*/

export class ClientClass {

/**

* When our client starts up, start a "reconnect 5 seconds

* from now" attempt, cleaned up when we connect.

*/

init() {

this.#resetState();

runLater(() => this.#tryReconnect(), RECONNECT_TIMEOUT_IN_MS);

}

/**

* A private function that sets our state to a "starting default" state.

*/

async #resetState() {

// "setState" is a magic function that comes with socketless, and will

// automatically lead to a browser sync, if there's a browser connected.

this.setState({

crashed: false,

flying: false,

MSFS: false,

serverConnection: false,

paused: true,

});

}

/**

* A private function that lets us reconnect to the server

* in case it disappears and comes back online.

*/

async #tryReconnect() {

if (this.server) {

clearTimeout(reconnection);

return console.log(`reconnected`);

}

console.log(`trying to reconnect to the server...`);

this.#resetState();

this.reconnect(); // <- this is also a magic socketless function

reconnection = setTimeout(

() => this.#tryReconnect(),

RECONNECT_TIMEOUT_IN_MS

);

}

/**

* The main role of our client is to encode a state that can be

* automatically communicated to the browser. As such, really

* the only thing we're doing si setting up a state, and then

* updating that based on server signals.

*/

async onConnect() {

clearTimeout(reconnection);

console.log(`client connected to server`);

this.setState({

serverConnection: true,

});

await this.server.api.register(`MSFS`);

}

/**

* If we become disconnected from the server, go into a

* "holding pattern" where we check whether the server

* is back every few seconds.

*/

async onDisconnect() {

// First, since we obviously don't have a server anymore,

// we won't be informed about whether or not we're still

// flying, or really anything about the flight at all, so

// record that we're not flying (anymore).

this.setState({

flying: false,

MSFS: false,

serverConnection: false,

});

// Then start the reconnect cycle

this.#tryReconnect();

}

// Record that a connection has been established. Since the state

// gets automatically synced at the browser, this means the browser

// can also see that `this.state.connected` is true.

async onBrowserConnect(browser) {

this.setState({ browserConnected: true });

}

// And the opposite when the browser disconnects, of course:

async onBrowserDisconnect(browser) {

this.setState({ browserConnected: false });

}

// Then a set of self-explanatory functions based on events:

async onMSFS(value) { this.setState({ MSFS: value }); }

async pause() { this.setState({ paused: true }); }

async unpause() { this.setState({ paused: false }); }

async crashed() { this.setState({ crashed: true }); }

async crashReset() { this.setState({ crashed: false }); }

}

With that, let’s move on to the browser.

The browser code

In order for the browser to be able to “do something”, we’ll use the index.html we made earlier without any modifications, but we’ll update index.js:

import { createBrowserClient } from "../socketless.js";

// Let's import a class that's *actually* going to do all the work...

import { Plane } from "./js/plane.js";

// And then we update our browser client, whose sole responsibility

// is to hand off state updates to our new "Plane" object:

class BrowserClient {

async init() {

this.plane = new Plane(this.server);

}

async update(prevState) {

// set a class on the HTML body based on our connection state...

document.body.classList.toggle(`connected`, this.state.serverConnection);

// And then, ather than "doing anything" here, we just pass the current

// state on to the Plane. All we do in this file is wait for the next update.

this.plane.updateState(this.state);

}

}

createBrowserClient(BrowserClient);

So that just leaves looking at our Plane code, which will minimal for now, andwe’ll put in public/js/plane.js:

// We'll be building this out throughout this document, but this

// will be our main entry point when it comes to what the browser

// shows in terms of both visualisation and interactivity.

export class Plane {

constructor(server) {

this.server = server;

this.lastUpdate = {

lat: 0,

long: 0,

flying: false,

crashed: false,

};

}

async updateState(state) {

this.state = state;

const now = Date.now();

// ...nothing here yet, but we'll be filling this out in soon enough!

this.lastUpdate = { time: now, ...state };

}

}

And that’s it. There’s nothing “meaningful” in our plane class yet, but for the moment we’re done: we’ve set up a complete API server, web server, and browser system.

Adding “permission control”

That just leaves one last thing: making sure that only “we” get to talk to MSFS directly. We don’t want people to just spam MSFS with API requests or even set values or trigger MSFS event and mess with our flight, or worse!

In order to do that, we first add three new keys to our .env file to act as a security key:

export API_PORT=8080

export WEB_PORT=3000

export FLIGHT_OWNER_KEY="dXNlcm5hbWVwYXNzd29yZA=="

export FLIGHT_OWNER_USERNAME=username

export FLIGHT_OWNER_PASSWORD=password

Just a base64 conversion of the string concatenation "username" + "password"… super secure! Of course, when we make our web page available, we’ll want to make triple-sure that we change this key to something a little more secret-appropriate =)

Then, let’s update our server.js class with a function that clients can call in order to authenticate:

...

const { FLIGHT_OWNER_KEY } = process.env;

...

export class ServerClass {

#authenticatedClients = [];

async init() {

const { clients } = this;

api = new MSFS_API();

// Set up call routing so that clients can call this.server.api.[...]

// in order to talk directly to the API, but only allow this for

// authenticated clients, rather than everyone:

this.api = this.lock(

new APIRouter(api),

(client) => this.#authenticatedClients.includes(client)

);

connectServerToAPI(api, async () => {

...

});

}

..

/**

* An almost trivially simple authentication function:

*/

async authenticate(client, username, password) {

// This should go without saying, but: don't do this in real

// code. Use a proper, secure login solution, instead =)

const hash = btoa(username + password);

if (hash !== FLIGHT_OWNER_KEY) return false;

console.log(`authenticated client ${client.id}`);

this.#authenticatedClients.push(client);

return true;

}

}

With that, we can now make clients (and by extension, browsers) authenticate by having them call this.server.authenticate(...), so let’s make that work by updating our client.js so it loads that key (if it has access to it) and calls the authentication function:

// Load in our environment variables now we have

import url from "node:url";

const __dirname = url.fileURLToPath(new URL(".", import.meta.url));

import dotenv from "dotenv";

dotenv.config({ path: `${__dirname}/../../../.env` });

// Do we have a flight owner key that we need to authenticate with?

let username, password;

if (process.argv.includes(`--owner`)) {

username = process.env.FLIGHT_OWNER_USERNAME;

password = process.env.FLIGHT_OWNER_PASSWORD;

}

...

export class ClientClass {

...

// The only update will be to our "onConnect", where we're

// going to immediately try to authenticate with the server:

async onConnect() {

clearTimeout(reconnection);

console.log(`client connected to server`);

this.setState({

// authenticate with the server, using our stored username and password:

authenticated: await this.server.authenticate(username, password),

serverConnection: true,

});

// Since API access is now restricted, make sure we only call it

// when we know (or think we know) that we won't be rejected.

if (this.state.authenticated) {

await this.server.api.register(`MSFS`);

}

}

...

}

And that’s our “authentication” added, so we have all the parts in place:

- we can start up MSFS,

- we can start up our API server using

node api-server.js, - we can start up our web server using

node web-server.js --owner --browser - we can have the browser open http://localhost:3000, and then

- we can use a UI that’s based on the current client state, with the option to get values from MSFS as well as set values and trigger events in MSFS as needed using the developer tools console.

Testing our code

So, let’s run this code and actually talk to MSFS. First, let’s make sure we have direct access to our browser client by updating our index.js:

...

// Let's get a direct reference to our client so we can do some testing using our developer tools:

window.browserClient = createBrowserClient(BrowserClient);

As you can see the createBrowserClient returns the actual instance it builds. There’s rarely a reason to capture that, but it can be very useful for testing, like now!

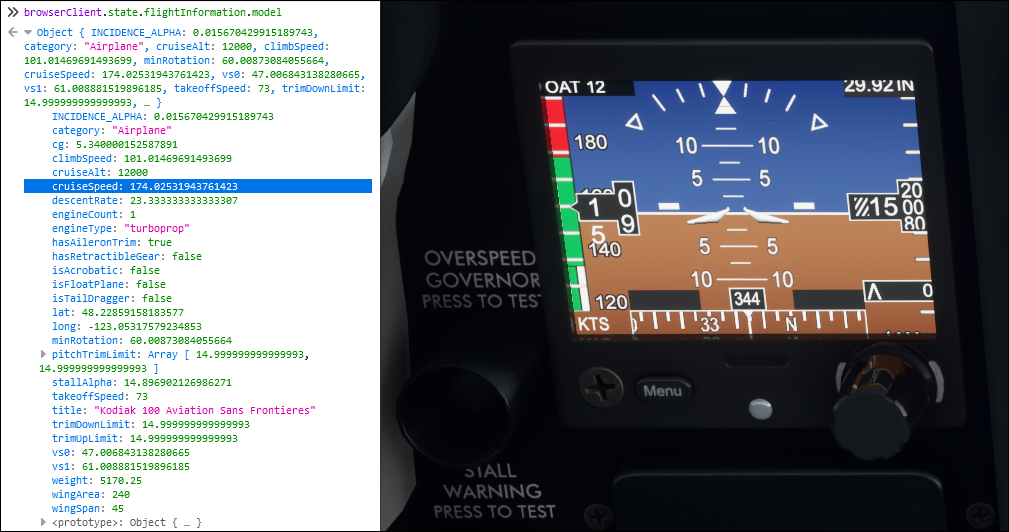

Let’s fire up MSFS and load up a plane on on a runway somewhere, run our API server, run our client with the --browser flag, and then let’s open the developer tools in the browser and get to the “console” tab. While there, let’s ask MSFS for some things:

» await browserClient.server.api.get(

`CATEGORY`,

`DESIGN_CRUISE_ALT`,

`DESIGN_TAKEOFF_SPEED`,

`ENGINE_TYPE`,

`IS_TAIL_DRAGGER`,

`NUMBER_OF_ENGINES`,

`TITLE`,

`TOTAL_WEIGHT`,

`TYPICAL_DESCENT_RATE`,

`WING_SPAN`,

);

If we had loaded up a De Havilland DHC-2 “Beaver”, we might get the following response:

« ▼ Object {

"CATEGORY": "Airplane",

"DESIGN_CRUISE_ALT": 5000,

"DESIGN_TAKEOFF_SPEED": 65,

"ENGINE_TYPE": 0,

"IS_TAIL_DRAGGER": 1,

"NUMBER_OF_ENGINES": 1,

"TITLE": "Blackbird Simulations DHC-2 Beaver Wheels N93E",

"TOTAL_WEIGHT": 3954.932373046875,

"TYPICAL_DESCENT_RATE": 16.66666666666665,

"WING_SPAN": 48

}

Of course, none of these things have units, but that’s what the SimConnect documentation is for: the Beaver is designed to cruise at 5000 feet, take off at 65 knots, it has a two wheels up front and a little wibble wheel at the back (i.e. it’s a “tail dragger”), it has one engine, which is a piston propeller (which we know by looking up the enum for engine type); it weighs 3955 pounds, has a wing span of 48 feet, and has a typical descent rate of 16.667 feet per second.

And of course, we can also ask for information that’s relevant to our flight right now rather than just asking about the plane in general. Say we actually took off and are cruising along, we can run:

» await browserClient.server.api.get(

`AIRSPEED_INDICATED`,

`ELEVATOR_TRIM_PCT`,

`PLANE_ALT_ABOVE_GROUND`,

`PLANE_ALTITUDE`,

`PLANE_BANK_DEGREES`,

`PLANE_HEADING_DEGREES_MAGNETIC`,

`PLANE_LONGITUDE`,

`PLANE_LATITUDE`,

`VERTICAL_SPEED`,

);

And this might give us something like:

« ▼ Object {

"AIRSPEED_INDICATED": 139.7057647705078,

"ELEVATOR_TRIM_PCT": -0.33069596466810336,

"PLANE_ALT_ABOVE_GROUND": 573.1917558285606,

"PLANE_ALTITUDE": 996.7162778193412,

"PLANE_BANK_DEGREES": -0.001284847042605199,

"PLANE_HEADING_DEGREES_MAGNETIC": 4.539803629684118,

"PLANE_LONGITUDE": -2.1609759665698802,

"PLANE_LATITUDE": 0.8514234731618152,

"VERTICAL_SPEED": 0.3496674597263333

}

This tells us our plane is flying over Vancouver Island at GPS coordinates -123.814803 longitude, 48.782971 latitude (both values reported in degrees radians by MSFS, not decimal degrees), with an air speed of about 140 knots (which is around 260kmh/161mph), flying at an altitude of almost 1000 feet (305m) above sea level, but really only about 573 feet (174m) above the ground. We can see that we’re flying fairly straight (our “bank” angle is basically 0), with a heading of 260 degrees on the compass (given in radians again), and we can see that we’re flying fairly straight in the vertical sense, too: the plane is currently moving up at about a third of a foot per second (so about 4”, or 10cm, per second), which is well within “flying straight” limits.

We can trigger events, too:

» await browserClient.server.api.get(`TAILWHEEL_LOCK_ON`);

» browserClient.server.api.trigger(`TOGGLE_TAILWHEEL_LOCK`);

» await browserClient.server.api.get(`TAILWHEEL_LOCK_ON`);

Which should result in:

« ▼ Object {

"TAILWHEEL_LOCK_ON": 0

}

« undefined

« ▼ Object {

"TAILWHEEL_LOCK_ON": 1

}

And of course, we can listen for events. For example, we can write this:

» browserClient.server.api.on(`CRASHED`, () => console.log(`...we crashed!`))

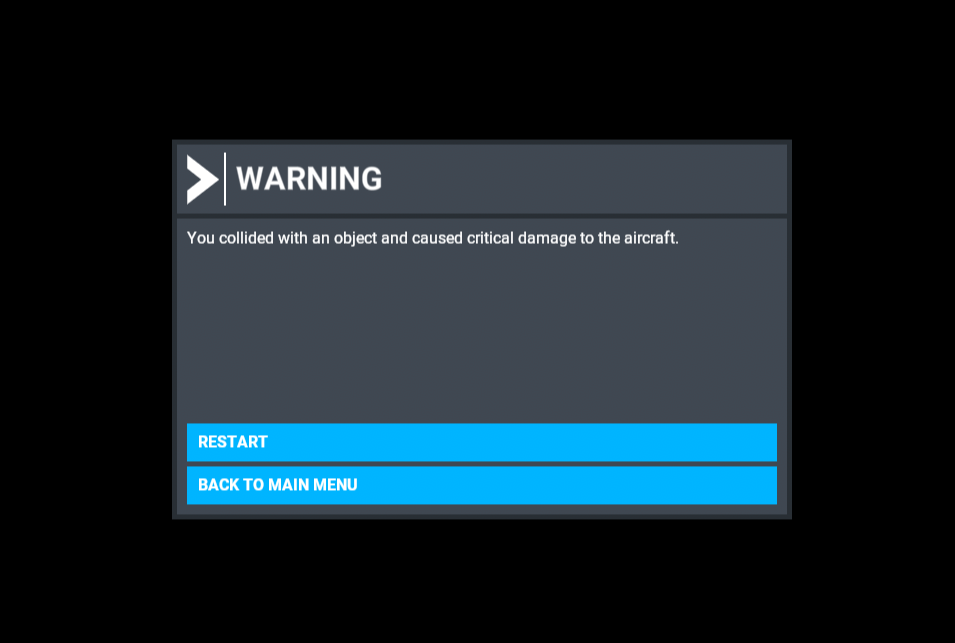

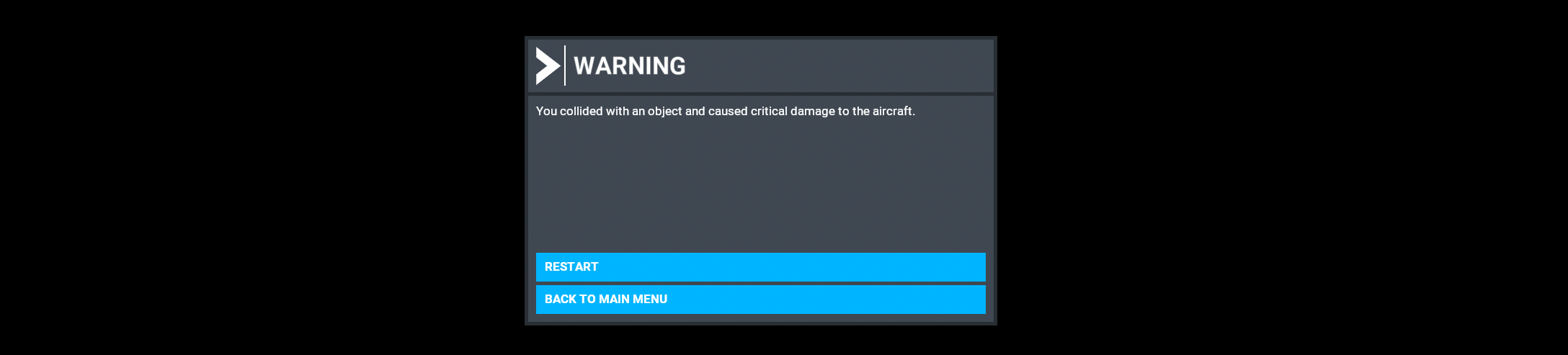

And now if we point our plane towards the ground and just let gravity do the rest (don’t worry, it’s just pixels, it’s perfectly safe), eventually our flight will come to an abrupt stop, the MSFS screen will go black, and we’ll get a little dialog telling us that we crashed… but if we look at the dev tools console for our web page, we’ll also see this little gem:

...we crashed!

Which means our crash event listener worked. So this is promising, we have a full loop!

Hot-reloading to make our dev lives easier

Now, being able to write code is all well and good, but we’re going to be working on that code a lot, so it’d be nice if we don’t constantly have to stop and restart the server for every line we change, and instead just have code changes kick in automatically when we save files. And while there isn’t anything baked into JS to make that happen, with a bit of smart programming we can take advantage of filesystem watching, as we well as how import works, to make this happen for us. Anyway

We can, for instance, write a function that will selectively watch a single file for changes, and if it sees any, load the new code in, and then trigger an event handler for “whoever might need it” with the newly loaded code:

// We'll be using Node's own file watch mechanism for this:

import { watchFile } from "node:fs";

// With some helpers for making sure we know where our files and modules live:

import { __root } from "./constants.js";

import { rootRelative } from "./utils.js";

export async function watch(basePath, modulePath, onChange) {

const filePath = basePath + modulePath;

const moduleURL = `file:///${filePath}`;

// Step 1: don't run file-watching in production. Obviously.

if (process.env.NODE_ENV === `production`) {

return import(moduleURL);

}

// Next, get the current callstack, so we can report on

// that when a file change warrants an update.

const callStack = new Error().stack

.split(`\n`)

.slice(2)

.map((v) => {

return v

.trim()

.replace(`file:///${__root}`, `./`)

.replace(/^at /, ` in `)

.replace(/new (\S+)/, `$1.constructor`);

})

.join(`\n`)

.replace(/\.constructor \(([^)]+)\)(.|[\n\r])*/, `.constructor ($1)`);

// If we're not running in production, check this file for changes every second:

watchFile(filePath, { interval: 1000 }, async () => {

console.log(`Reloading module ${rootRelative(filePath)} at ${Date.now()}`);

try {

// If there was a change, re-import this file as an ES module, with a "cache busting" URL

// that includes the current time stamp. Modules are cached based on their exact URL,

// so adding a query argument that we can vary means we can "reimport" the code:

const module = await import(`${moduleURL}?ts=${Date.now()}`);

// Then we log the stack so we know where this reload was set up in our code:

console.log(callStack);

// To confirm to ourselves that a module was fully loaded as a "new module" we check

// whether it has a `LOAD_TIME` constant that it set during load, and log what that

// value is. Because it should be very close to our reload time.

if (module.LOAD_TIME)

console.log(` Module-indicated load time is ${module.LOAD_TIME}`);

// And then we run whatever code needs to run now that the module's been reloaded.

onChange(module);

} catch (e) {

// Never crash the server just because someone saved a file with a typo.

console.error(`\nWatcher could not load module: ${filePath}`);

console.error(callStack);

console.error(e);

}

});

// Then, as part of the call, run an immediate load with a timestamp, so we're cache-busting.

return import(`${moduleURL}?ts=${Date.now()}`);

}

With the extra imported bits, from src/utils/constants.js:

// Get the directory that this file lives in:

import url from "node:url";

const __dirname = url.fileURLToPath(new URL(".", import.meta.url));

// And then use that to figure out what the project root dir is:

import { join, resolve, sep, win32, posix } from "node:path";

export const __root = (resolve(join(__dirname, `..`, `..`)) + sep).split(win32.sep).join(posix.sep);

and src/utils/utils.js:

import { win32, posix } from "node:path";

// Get a file's path relative to the project root directory

export function rootRelative(filepath) {

return filepath.split(win32.sep).join(posix.sep).replace(__root, `./`);

}

The thing that makes this work is usually considered a memory leak: modules are cached based on their URL, and URL query arguments count towards URL “uniqueness”, so by loading the module using a URL ending in ...?ts=${Date.now()} we effectively load a separate, new module, thus bypassing the module caching mechanism.

That sounds great, but because there is no mechanism for “unloading” modules is modern JS, every save-and-reload will effectively cause a new file to be loaded in, without the old file getting unloaded, so we’re going to slowly fill up our memory… which would be a problem if our files weren’t tiny compared to how much memory modern computers (or even cell phones for that matter), have. So this is going to be a non-issue, but it’s still good to know about, and an excellent idea to make sure it doesn’t kick in for production code.

A more practical problem, though, is that we can no longer “just import something from a module”, because imports are considered constants, with import { x } from Y being equivalent to declarig a const x = ..., so we can’t “reimport” onto the same variable name. That would be a runtime error.

Instead, we need to be a little more clever about how we import code: we can use a top-level await to make the watcher load the module we want, and assign that to a mutable variable:

// Get the url for "this script", since that's what relative imports will be relative to:

import url from "node:url";

const __dirname = url.fileURLToPath(new URL(".", import.meta.url));

// Then import our watcher:

import { watch } from "./reload-watcher.js";

// Then, as mentioned above, we load our import as a mutable variable instead of "as an import":

let { Something } = await watch(__dirname, `some-module.js`, (lib) => {

Something = lib.Something;

});

And while that’s a bit more code, and requires an await (which is easy to forget!) now every time we edit some-module.js and save it, the watcher will reload that code for us and our Something variable will get updated. So that solved half of the reloading problem. The other half is making sure that if our module exports a class, that instances of that class get updated, too, by taking advantage of how prototype inheritance works in JS.

Since objects don’t have their type “baked in”, but simply follow a chain of prototype objects, we can change one of those prototype objects and basically change the identity of the object itself. Normally, this would be a bad idea(tm) but in this specific case, it’s exactly what we need to make sure that instances of any hot-reloadable classes we use get updated as part of the reload process:

// We can set up our reload watcher to update not just the

// variable for our class, but also instances of that class:

let { Something } = await watch(__dirname, `some-module.js`, (lib) => {

// Update our class binding:

Something = lib.Something;

// And then update our class instance's prototype. This only works because

// by the time this code runs, the "instance" variable will exist.

if (instance) {

Object.setPrototypeOf(instance, Something.prototype);

// This swaps the old prototype for the new code, while leaving any

// of the instance's own properties unaffected. Something that will be

// particularly useful for changing autopilot code *while* we're flying!

}

});

let instance = new Something();

Part 2: visualizing flights

Before we try to automate flight by writing an autopilot, it helps if we can know what “a flight” is. I mean, you and I know what a flight is, but computers not so much, especially when they can’t even see your game, so let’s figure out what information we need our code to know about before we can ask it to do the things we might want it to do.

Checking the game data: what do we want to know?

There are two kinds of information that we’ll want our code to know about: “static” information like the name of the plane we’re flying, whether it has a tail wheel, how much it weighs, etc. and “dynamic information” like what lat/long the plane is current at, how fast it’s going, what its current pitch angle is, etc.

We can compile a list of properties that we’re likely going to need in order to write our autopilot, and then request all those values from MSFS at a regular interval using SimConnect, so that we can then forward that information to our autopilot code, as well as all clients, and consequently, any connected browser.

Getting game state data

So let’s write some code that lets us relatively easily work with flight models and flight data. We’ll create a src/utils/flight-values.js file, and then start with the list flight model values we’ll want:

export const FLIGHT_MODEL = [

`CATEGORY`,

`DESIGN_CRUISE_ALT`,

`DESIGN_SPEED_CLIMB`,

`DESIGN_SPEED_MIN_ROTATION`,

`DESIGN_SPEED_VC`,

`DESIGN_SPEED_VS0`,

`DESIGN_SPEED_VS1`,

`DESIGN_TAKEOFF_SPEED`,

`ELEVATOR_TRIM_DOWN_LIMIT`,

`ELEVATOR_TRIM_UP_LIMIT`,

`ENGINE_TYPE`,

`INCIDENCE_ALPHA`,

`IS_GEAR_FLOATS`,

`IS_GEAR_RETRACTABLE`,

`IS_TAIL_DRAGGER`,

`NUMBER_OF_ENGINES`,

`PLANE_LATITUDE`,

`PLANE_LONGITUDE`,

`STALL_ALPHA`,

`STATIC_CG_TO_GROUND`,

`TITLE`,

`TOTAL_WEIGHT`,

`TYPICAL_DESCENT_RATE`,

`WING_AREA`,

`WING_SPAN`,

];

export const ENGINE_TYPES = [

`piston`,

`jet`,

`none`,

`helo(Bell) turbine`,

`unsupported`,

`turboprop`,

];

Do we need all that data? Surprisingly: yes! Almost all of these will let us either bootstrap our autopilot parameters, or will let us show things we’re interested in on our web page.

Next up, our “things we want to know while we’re actually flying” data:

export const FLIGHT_DATA = [

`AILERON_POSITION`,

`AILERON_TRIM_PCT`,

`AIRSPEED_INDICATED`,

`AIRSPEED_TRUE`,

`AUTOPILOT_HEADING_LOCK_DIR`,

`AUTOPILOT_MASTER`,

`CAMERA_STATE`,

`CAMERA_SUBSTATE`,

`CRASH_FLAG`,

`CRASH_SEQUENCE`,

`ELECTRICAL_AVIONICS_BUS_VOLTAGE`,

`ELECTRICAL_TOTAL_LOAD_AMPS`,

`ELEVATOR_POSITION`,

`ELEVATOR_TRIM_PCT`,

`ELEVATOR_TRIM_POSITION`,

`ENG_COMBUSTION:1`,

`ENG_COMBUSTION:2`,

`ENG_COMBUSTION:3`,

`ENG_COMBUSTION:4`,

`GEAR_POSITION:1`,

`GEAR_SPEED_EXCEEDED`,

`GROUND_ALTITUDE`,

`INDICATED_ALTITUDE`,

`OVERSPEED_WARNING`,

`PLANE_ALT_ABOVE_GROUND_MINUS_CG`,

`PLANE_ALT_ABOVE_GROUND`,

`PLANE_BANK_DEGREES`,

`PLANE_HEADING_DEGREES_MAGNETIC`,

`PLANE_HEADING_DEGREES_TRUE`,

`PLANE_LATITUDE`,

`PLANE_LONGITUDE`,

`PLANE_PITCH_DEGREES`,

`RUDDER_POSITION`,

`RUDDER_TRIM_PCT`,

`SIM_ON_GROUND`,

`TURN_INDICATOR_RATE`,

`VERTICAL_SPEED`,

];

This also looks like a lot of data, but we really do need every single one of these values if we’re going to implement an autopilot.

Converting SimConnect values

But: this does leave us with a problem: SimConnect isn’t really all that fussy about making sure every single value uses a unit that makes sense, or that collections of variables all use the same unit, so we’re in a situation where something like PLANE_BANK_DEGREES, which you would expect to be a number in degrees, is actually a number in radians. And AIRSPEED_TRUE is in knots, so surely DESIGN_SPEED_CLIMB is in knots, too, right? Nope, that’s in feet per second. Which means DESIGN_SPEED_VS1 is in feet per second, too? Haha, no, that one is in knots, but “knots indicated”, so not a real speed, but what the dial in the cockpit shows on the speed gauge. Oh, and: boolean values aren’t true or false, they’re 1 or 0.

It’s all a bit of a mess, so let’s write some code to take of all this nonsense and make sure values are in units we can rely on, because if we don’t it’s just going to be a huge headache:

// These are all degree values that are actually stored as radians.

export const DEGREE_VALUES = [

`PLANE_LATITUDE`,

`PLANE_LONGITUDE`,

`PLANE_BANK_DEGREES`,

`PLANE_HEADING_DEGREES_MAGNETIC`,

`PLANE_HEADING_DEGREES_TRUE`,

`PLANE_PITCH_DEGREES`,

`STALL_ALPHA`,

`TURN_INDICATOR_RATE`,

];

// These are all boolean values that are stored as a number.

export const BOOLEAN_VALUES = [

`AUTOPILOT_MASTER`,

`ENG_COMBUSTION:1`,

`ENG_COMBUSTION:2`,

`ENG_COMBUSTION:3`,

`ENG_COMBUSTION:4`,

`IS_GEAR_FLOATS`,

`IS_GEAR_RETRACTABLE`,

`IS_TAIL_DRAGGER`,

`GEAR_POSITION:1`,

`GEAR_SPEED_EXCEEDED`,

`OVERSPEED_WARNING`,

`SIM_ON_GROUND`,

];

// These are percentages, but stored as "percent divided by 100"

export const PERCENT_VALUES = [

`AILERON_POSITION`,

`AILERON_TRIM_PCT`,

`ELEVATOR_POSITION`,

`ELEVATOR_TRIM_PCT`,

`RUDDER_POSITION`,

`RUDDER_TRIM_PCT`,

];

// In game, vertical speed is shown feet per minute,

// but SimConnect reports it as feet per second...

export const FPM_VALUES = [`VERTICAL_SPEED`];

// Plane altitude is in feet, so why is ground altitude in meters?

export const MTF_VALUES = [`GROUND_ALTITUDE`];

// And finally, please just turn all of these into

// values in knots instead of feet per second...

export const KNOT_VALUES = [

`DESIGN_SPEED_MIN_ROTATION`,

`DESIGN_SPEED_CLIMB`,

`DESIGN_SPEED_VC`,

];

We can pair this with a function that runs through a bunch of rewrites for each of the categories, to give us values to work with that actually make sense:

import { FEET_PER_METER, FPS_IN_KNOTS } from "./constants.js";

import { exists } from "./utils.js";

const noop = () => {};

export function convertValues(data) {

// Convert values to the units they're supposed to be:

BOOLEAN_VALUES.forEach((p) => exists(data[p]) ? (data[p] = !!data[p]) : noop);

DEGREE_VALUES.forEach((p) => exists(data[p]) ? (data[p] *= 180 / Math.PI) : noop);

PERCENT_VALUES.forEach((p) => (exists(data[p]) ? (data[p] *= 100) : noop));

FPM_VALUES.forEach((p) => exists(data[p]) ? (data[p] *= 60) : noop);

KNOT_VALUES.forEach((p) => exists(data[p]) ? (data[p] *= FPS_IN_KNOTS) : noop);

MTF_VALUES.forEach((p) => exists(data[p]) ? (data[p] *= FEET_PER_METER) : noop);

if (exists(data.ENGINE_TYPE)) data.ENGINE_TYPE = ENGINE_TYPES[data.ENGINE_TYPE];

}

In this code, the contants that we import have the values 364000, 3.28084, and 1/1.68781, respectively, and the exists function is just a tiny function that checks whether a value is either undefined or null, because we want to overwrite a value if it exist, rather than if it doesn’t exist, and there is no opposite of the ??= operator.

Which leaves one more thing: calming all those words down a little, because working with PLANE_ALT_ABOVE_GROUND_MINUS_CG or AUTOPILOT_HEADING_LOCK_DIR is something we could do, but it would be a heck of a lot nicer if those things had normal names that followed standard JS naming conventions.

So let’s write even more utility code to take care of that for us:

export const NAME_MAPPING = {

AILERON_POSITION: `aileron`,

AILERON_TRIM_PCT: `aileronTrim`,

AIRSPEED_INDICATED: `speed`,

AIRSPEED_TRUE: `trueSpeed`,

AUTOPILOT_HEADING_LOCK_DIR: `headingBug`,

AUTOPILOT_MASTER: `MASTER`,

CAMERA_STATE: `camera`,

CAMERA_SUBSTATE: `cameraSub`,

CATEGORY: `category`,

CRASH_FLAG: `crashed`,

CRASH_SEQUENCE: `crashSequence`,

DESIGN_CRUISE_ALT: `cruiseAlt`,

DESIGN_SPEED_CLIMB: `climbSpeed`,

DESIGN_SPEED_MIN_ROTATION: `minRotation`,

DESIGN_SPEED_VC: `cruiseSpeed`,

DESIGN_SPEED_VS0: `vs0`,

DESIGN_SPEED_VS1: `vs1`,

DESIGN_TAKEOFF_SPEED: `takeoffSpeed`,

ELECTRICAL_AVIONICS_BUS_VOLTAGE: `busVoltage`,

ELECTRICAL_TOTAL_LOAD_AMPS: `ampLoad`,

ELEVATOR_POSITION: `elevator`,

ELEVATOR_TRIM_DOWN_LIMIT: `trimDownLimit`,

ELEVATOR_TRIM_PCT: `pitchTrim`,

ELEVATOR_TRIM_POSITION: `trimPosition`,

ELEVATOR_TRIM_UP_LIMIT: `trimUpLimit`,

ENGINE_TYPE: `engineType`,

"GEAR_POSITION:1": `isGearDown`,

GEAR_SPEED_EXCEEDED: `gearSpeedExceeded`,

GROUND_ALTITUDE: `groundAlt`,

INDICATED_ALTITUDE: `alt`,

IS_GEAR_FLOATS: `isFloatPlane`,

IS_GEAR_RETRACTABLE: `hasRetractibleGear`,

IS_TAIL_DRAGGER: `isTailDragger`,

NUMBER_OF_ENGINES: `engineCount`,

OVERSPEED_WARNING: `overSpeed`,

PLANE_ALT_ABOVE_GROUND_MINUS_CG: `lift`,

PLANE_ALT_ABOVE_GROUND: `altAboveGround`,

PLANE_BANK_DEGREES: `bank`,

PLANE_HEADING_DEGREES_MAGNETIC: `heading`,

PLANE_HEADING_DEGREES_TRUE: `trueHeading`,

PLANE_LATITUDE: `lat`,

PLANE_LONGITUDE: `long`,

PLANE_PITCH_DEGREES: `pitch`,

RUDDER_POSITION: `rudder`,

RUDDER_TRIM_PCT: `rudderTrim`,

SIM_ON_GROUND: `onGround`,

STATIC_CG_TO_GROUND: `cg`,

STALL_ALPHA: `stallAlpha`,

TITLE: `title`,

TOTAL_WEIGHT: `weight`,

TURN_INDICATOR_RATE: `turnRate`,

TYPICAL_DESCENT_RATE: `descentRate`,

VERTICAL_SPEED: `VS`,

WING_AREA: `wingArea`,

WING_SPAN: `wingSpan`,

};

export function renameData(data) {

Object.entries(data).forEach(([simName, value]) => {

const jsName = NAME_MAPPING[simName];

if (jsName === undefined) return;

if (!exists(data[simName])) return;

data[jsName] = value;

delete data[simName];

});

}

And that’s us nearly here. However, SimConnect typically only serves up “values” and if we’re going to write an autopilot, we generally also care the change in certain values over time. For instance, just knowing our current vertical speed doesn’t tell us whether we’re ascending or descending, and just knowing that we’re turning at 3 degrees per second right now doesn’t tell us anything about whether we’re about to spiral out of control or whether we’re about to stop turning entirely.

So we need a little bit of extra code to track the “delta” values for some of the flight properties we listed earlier:

// Our list of "first derivatives", i.e. our deltas

export const DERIVATIVES = [

`bank`,

`heading`,

`lift`,

`pitch`,

`speed`,

`trueHeading`,

`trueSpeed`,

`turnRate`,

`VS`,

];

// And our single "second derivative":

export const SECOND_DERIVATIVES = [`VS`];

// And then an update to the `rebind` function:

export function renameData(data, previousValues) {

// Whether or not we have previous values for delta computation,

// just preallocate the values we _might_ need for that.

const d = {};

const now = Date.now();

const before = previousValues?.__date_time ?? now;

const dt = (now - before) / 1000; // delta per second seconds

// Then perform the name mapping, but with extra code for getting

// our "delta" values, which we'll add into a `.d` property.

Object.entries(data).forEach(([simName, value]) => {

const jsName = NAME_MAPPING[simName];

if (jsName === undefined) return;

if (!exists(data[simName])) return;

data[jsName] = value;

delete data[simName];

// Do we need to compute derivatives?

if (previousValues && DERIVATIVES.includes(jsName)) {

const previous = previousValues[jsName];

if (typeof previous !== `number`) return;

const current = data[jsName];

d[jsName] = (current - previous) / dt;

// ...do we need to compute *second* derivatives?

if (SECOND_DERIVATIVES.includes(jsName)) {

d.d ??= {};

const previousDelta = previousValues.d?.[jsName] ?? 0;

d.d[jsName] = d[jsName] - previousDelta;

}

}

});

// If we did delta computation work, save the result:

if (previousValues) {

data.__date_time = now;

data.d = d;

}

}

Well that only took forever…

Our FlightInformation object

And we still need to write the actual code that actually pulls this data from SimConnect to keep us up to date. Thankfully, with all the above work completed, that part is nowhere near as much work. First, we write a FlightInformation object to wrap all those values and functions:

import {

FLIGHT_MODEL,

FLIGHT_DATA,

convertValues,

renameData,

} from "./flight-values.js";

let api;

export class FlightInformation {

constructor(_api) {

api = _api;

this.reset();

}

reset() {

this.model = false;

this.data = false;

this.general = {

flying: false,

inGame: false,

moving: false,

planeActive: false,

};

}

// We'll have three update functions. Two for the two types

// of data, and then this one, which is a unified "call both":

async update() {

try {

if (!api.connected) throw new Error(`API not connected`);

await Promise.all([this.updateModel(), this.updateFlight()]);

} catch (e) {

console.warn(e);

}

return this;

}

// Then our "update the model" code:

async updateModel() {

const data = await api.get(...FLIGHT_MODEL);

if (!data) return (this.flightModel = false);

// Make sure to run our quality-of-life functions:

convertValues(data);

renameData(data);

// Create a convenience value for trimming

data.pitchTrimLimit = [data.trimUpLimit ?? 10, data.trimDownLimit ?? -10];

return (this.model = data);

}

// And our "update the current flight information" code:

async updateFlight() {

const data = await api.get(...FLIGHT_DATA);

if (!data) return (this.data = false);

// Make sure to run our quality-of-life functions here, too:

convertValues(data);

renameData(data, this.data);

// Create a convenience value for "are any engines running?",

// which would otherwise require checking four separate variables:

data.enginesRunning = [1, 2, 3, 4].reduce(

(t, num) => t || data[`ENG_COMBUSTION:${num}`],

false

);

// Create a convenience value for "is the plane powered on?",

// which would otherwise require checking two variables:

data.hasPower = data.ampLoad !== 0 || data.busVoltage !== 0;

// And create a convenience value for compass correction:

data.declination = data.trueHeading - data.heading;

// Then update our general flight values and return;

this.setGeneralProperties(data);

return (this.data = data);

}

// The general properties are mostly there so we don't have to

// constantly derive them on the client side:

setGeneralProperties(data) {

const { onGround, hasPower, enginesRunning, speed, camera } = data;

const inGame = 2 <= camera && camera < 9;

const flying = inGame ? !onGround : false;

const moving = inGame ? speed > 0 : false;

const planeActive = inGame ? hasPower || enginesRunning : false;

Object.assign(this.general, { flying, inGame, planeActive, moving });

}

}

And then, as last step, we now need to make the server actually use this object, and make sure that clients can receive it. So, on the server side:

...

// Import our hot-reloader

import { watch } from "../../utils/reload-watcher.js";

// Import our fancy new class, in a way that lets us hot-reload it:

let flightInformation;

let { FlightInformation } = await watch(

__dirname,

`../../utils/flight-information.js`,

(module) => {

FlightInformation = module.FlightInformation;

if (flightInformation) {

Object.setPrototypeOf(flightInformation, FlightInformation.prototype);

}

}

);

class Server {

...

async init() {

...

connectServerToAPI(api, async () => {

console.log(`Connected to MSFS.`);

// Set up a flight information object for pulling

// model and flight data from SimConnect:

flightInformation = new FlightInformation(api);

registerWithAPI(clients, api, autopilot);

clients.forEach((client) => client.onMSFS(true));

(async function poll() {

// And make sure to pass this into our game check.

checkGameState(clients, flightInformation);

runLater(poll, POLLING_INTERVAL);

})();

});

}

async onConnect(client) {

if (api?.connected) client.onMSFS(true);

// When clients connect, immediately send them the most up to date

// flight information, if the flightInformation object has been

// initialized, of course.

if (flightInformation) {

client.setFlightInformation(flightInformation);

}

}

}

With the flightInformation added to the checkGameState function we created earlier in the helpers file:

// get the most up to date game state and send that over to our clients:

export async function checkGameState(clients, flightInformation) {

await flightInformation.update();

clients.forEach((client) => client.setFlightInformation(flightInformation));

}

And then we add the setFlightInformation function to the client class, to close the loop:

...

export class ClientClass {

...

// our base state now includes the flightinformation properties:

#resetState() {

this.setState({

...

flightInformation: {}

});

}

...

async setFlightInformation(flightInformation) {

// Just straight-up copy all the flight information state

// values, which will then automatically update any browser

// that's connected, as well.

this.setState({ flightInformation });

}

}

Well that only took forever, but we can finally get back to <checks notes> ticking a few HTML checkboxes?

Showing the game data

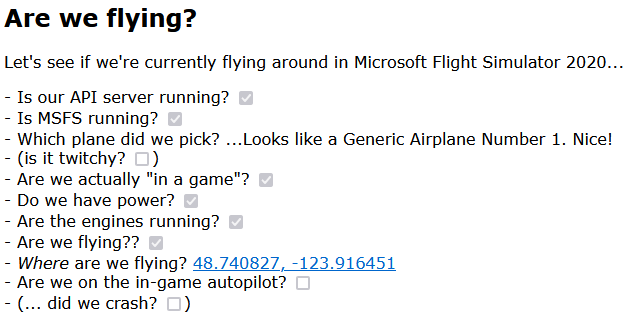

We know when we’re connected to MSFS, so let’s write a few functions that let us cascade through the various stages of the game before we get to “actually controlling a plane”. Let’s start with what we want that to look like:

Nothing particularly fancy (although we can pretty much use any amount of CSS to turn it into something fancy), but it lets us see where in the process of firing up MSFS, clicking through to the world map, and starting a flight we are. So let’s update our HTML file to include these questions, and then we can update our JS to start answering them:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="css/questions.css" />

<li>

Is our API server running? <input type="checkbox" disabled class="server-online" />

</li>

<li>

Is MSFS running? <input type="checkbox" disabled class="msfs-running" />

</li>

<li>

Which plane did we pick? <span class="specific-plane">... nothing yet?</span>

</li>

<li>

Are we actually "in a game"? <input type="checkbox" disabled class="in-game" />

</li>

<li>

Do we have power? <input type="checkbox" disabled class="powered-up" />

</li>

<li>

Are the engines running? <input type="checkbox" disabled class="engines-running" />

</li>

<li>

Are we flying?? <input type="checkbox" disabled class="in-the-air" />

</li>

<li>

<em>Where</em> are we flying?

<a href="." class="gmaps-link">

<span class="latitude">-</span>,

<span class="longitude">-</span>

</a>

</li>

<li>

Are we on the in-game autopilot? <input type="checkbox" disabled class="using-ap" />

</li>

<li>

(... did we crash? <input type="checkbox" disabled class="plane-crashed" />)

</li>

Excellent: boring, but serviceable, so let’s add a parent for that in our index.html:

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en-GB">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<title>Let's test our connections!</title>

<script src="js/index.js" type="module" async></script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Are we flying?</h1>

<p>

Let's see if we're currently flying around in Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020...

</p>

<ul>

<ul id="questions" data-description="Templated from questions.html"></ul>

</body>

</html>

And create a little CSS file in public/css/questions/css:

#questions {

list-style: none;

margin: 1em;

padding: 0;

text-indent: 0;

}

#questions li { display: block; }

#questions li:before { content: "-"; }

Then let’s move on to the JS side! First let’s write a little convenience file called questions.js that we’re going to use to (un)check these questions, based on the fact that we have access to the web client’s state:

const content = await fetch("questions.html").then((res) => res.text());

const questions = document.getElementById(`questions`);

questions.innerHTML = content;

// The query selectors for our elements:

const qss = [

`server-online`,

`msfs-running`,

`in-game`,

`powered-up`,

`engines-running`,

`in-the-air`,

`using-ap`,

`plane-crashed`,

`specific-plane`,

`gmaps-link`,

`latitude`,

`longitude`,

];

// A bit of house-keeping

const vowels = [`a`, `i`, `u`, `e`, `o`, `A`, `I`, `U`, `E`, `O`];

function titleCase(s) {

return s.substring(0, 1).toUpperCase() + s.substring(1).toLowerCase();

}

function reCase(e) {

return e

.split(`-`)

.map((s, p) => (p === 0 ? s : titleCase(s)))

.join(``);

}

// Let's create an object that's { serverOnline: span, msfsRunning: span, ... }

// because that'll make it easier to set text and check checkboxes:

const elements = Object.fromEntries(

qss.map((e) => {

const propName = reCase(e);

return [propName, document.querySelector(`.${e}`)];

})

);

// And then our questions helper: we're simply going to set every checkbox

// based on what's in the current state, only spending a little more time

// on the plane model, and mostly because we want the right "a" vs. "an"

// depending on whether the title starts with a vowel or not:

export const Questions = {

update(state) {

const {

general,

model: flightModel,

data: flightData,

} = state.flightInformation;

elements.serverOnline.checked = !!state.serverConnection;

elements.msfsRunning.checked = state.MSFS;

elements.inGame.checked = general?.inGame;

elements.poweredUp.checked = flightData?.hasPower;

elements.enginesRunning.checked = flightData?.enginesRunning;

elements.inTheAir.checked = general?.flying;

elements.usingAp.checked = flightData?.MASTER;

elements.planeCrashed.checked = state.crashed;

// And we'll do these two separately because they're a bit more than just a check mark:

this.whereAreWeFlying(flightData);

this.modelLoaded(flightModel?.title);

},

whereAreWeFlying(flightData) {

const lat = flightData?.lat?.toFixed(6);

const long = flightData?.long?.toFixed(6);

elements.gmapsLink.href = `https://www.google.com/maps/place/${lat}+${long}/@${lat},${long},13z`;

elements.latitude.textContent = lat ?? `-`;

elements.longitude.textContent = long ?? `-`;

},

modelLoaded(modelName) {

let model = `(...nothing yet?)`;

if (modelName) {

let article = `a`;

if (vowels.includes(modelName.substring(0, 1))) article += `n`;

model = `...Looks like ${article} ${modelName}. Nice!`;

}

elements.specificPlane.textContent = model;

},

};

Cool! Of course, this does nothing yet, so let’s plug it into our plane.js so that we can run through our sequence of “where in the game we are” as part of the update call:

...

import { Questions } from "./questions.js";

export class Plane {

...

async updateState(state) {

this.state = state;

const now = Date.now();

// Update our questions:

Questions.update(state);

this.lastUpdate = { time: now, ...state };

}

}

And that’s the “game state” read-back sorted out! Easy-peasy!

Trying our question list out

So: let’s tick some HTML checkboxes!

- Start MSFS,

- then up the server with

node api-server.jsand our client withnode web-server.js --browser, - then look at what happens in the browser as MSFS finished starting up.

- Load up a plane on a runway somewhere, and see what happens.

- Load up a plane mid-flight and see what the checkboxes do! And of course,

- look at what happens when you shut down MSFS, and what happens when you shut down the API server before you shut down the web client.

So, on the one hand: that was a LOT of work just to check some boxes! But the upside is that with all of that work out of the way, we’re done in terms of “making sure we have up to date information to work with”: all we need to do is call our flight information update function on the server side, and hook into our Plane’s updateState function on the browser side from now on, and that’s going to make things like running autopilot code and showing flight visualizations a lot easier.

And speaking of visualizations…

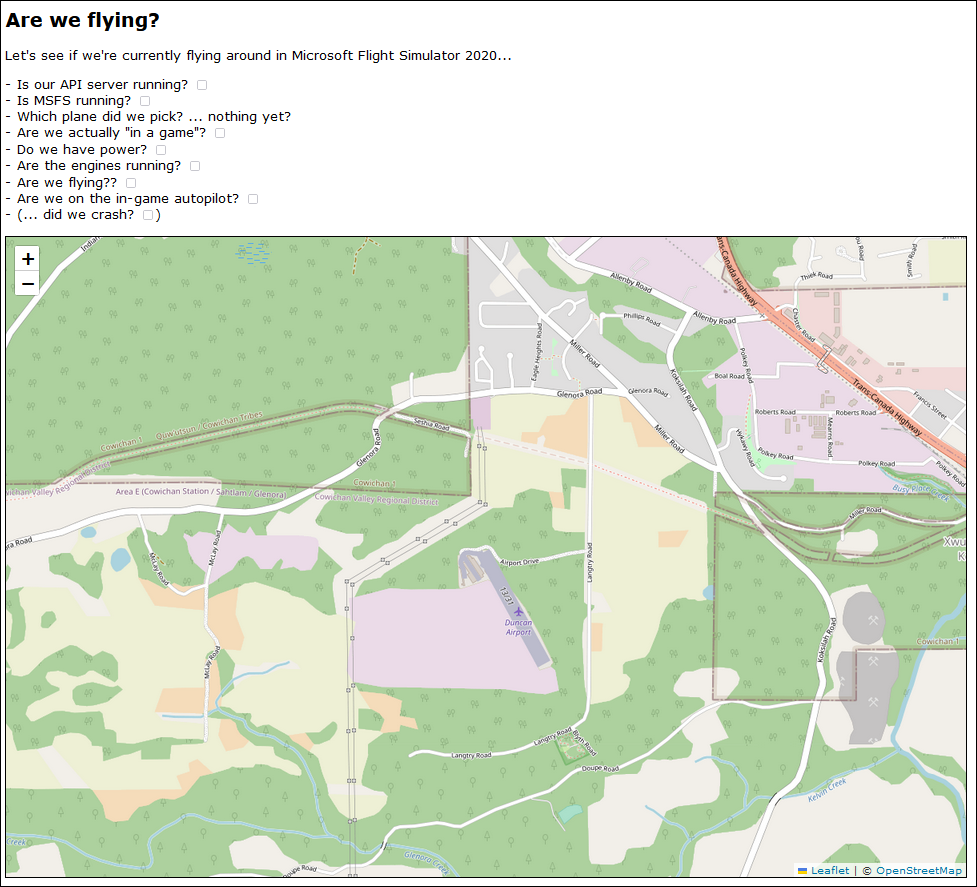

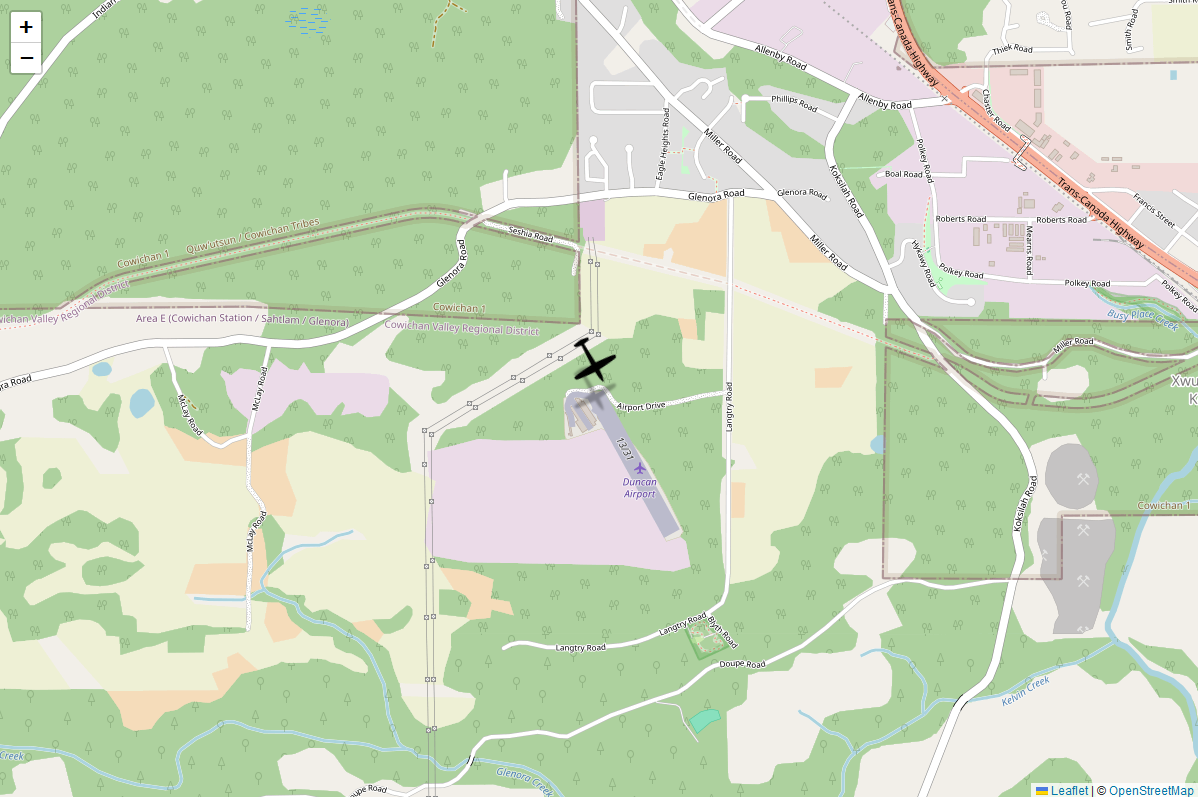

Putting our plane on the map

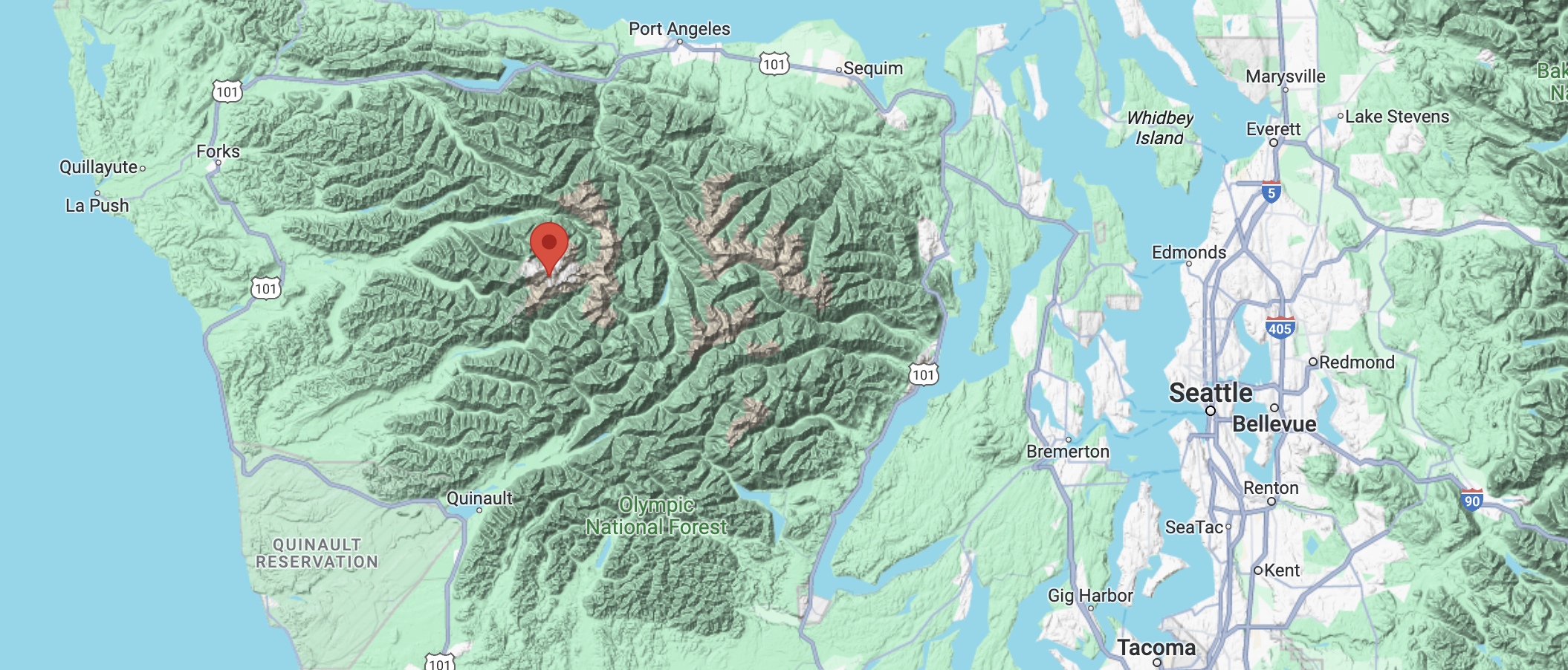

Even with all that work done, we’ve still only implemented page code that lets us answer a bunch of questions, but that’s hardly the only thing we’ll want to see on our page. Let’s add something that let’s us actually see something cool on our webpage: let’s set up a Leaflet map that we can put our plane on, so we can see ourselves flying around on a map.

Step one: update our index.html to make that work, including downloading Leaflet and putting it in public/js/leaflet. We could run it from CDN, using something like this:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/leaflet/1.9.4/leaflet.min.css" async />

<script src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/leaflet/1.9.4/leaflet.min.js" defer async></script>

And I encourage you to give that a try, but if we do, Leaflet takes “forever” to load, as opposed to loading near instantly if we save and use a local copy, so: download the .js and .css files from the above CDN links, and put them in our own leaflet dir, and then lets add them to our index.html as:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en-GB">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<title>Let's test our connections!</title>

<!-- we'll load Leaflet from CDN -->

<link rel="stylesheet" href="js/leaflet/leaflet.min.css" async />

<script src="js/leaflet/leaflet.min.js" defer async></script>

<!-- and then our own script -->

<script src="js/index.js" type="module" async></script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Are we flying?</h1>

<p>

Let's see if we're currently flying around in Microsoft Flight Simulator

2020...

</p>

<ul id="questions" data-description="Templated from questions.html"></ul>

<div id="visualization">

<!-- Then we'll hook Leaflet into the following div: -->

<div id="map" style="width: 1200px; height: 800px"></div>

</div>

</body>

</html>

And then let’s write a public/js/map.js that we can import to take care of the map for us:

import { waitFor } from "./utils.js";

export const DUNCAN_AIRPORT = [48.7566, -123.71134];

// Leaflet creates a global "L" object to work with, so use that to tie into the <div id="map"></div> we have sitting

// in our index.html. However, because independent page scripts can't be imported, we need to wait for it to be available:

const L = await waitFor(async () => window.L);

// With our "L" object available, let's make a map, centered on Duncan airport:

export const map = L.map("map").setView(DUNCAN_AIRPORT, 15);

// Of course, this won't *show* anything: we still need an actual map tile layer:

L.tileLayer(`https://tile.openstreetmap.org/{z}/{x}/{y}.png`, {

maxZoom: 19,

attribution: `© <a href="http://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright">OpenStreetMap</a>`,

}).addTo(map);

With a quick look at that waitFor function in public/js/utils.js:

// Return a promise that doesn't resolve until `fn()` returns a truthy value, or we run out of retries.

export function waitFor(fn, timeout = 5000, retries = 100) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

(async function run() {

if (--retries === 0) reject(new Error(`max retries reached`));

try {

const data = await fn();

if (!data) return setTimeout(run, timeout, retries);

resolve(data);

} catch (e) {

reject(e);